ISIS Detainees Crisis in Northeast Syria.. Between Military Victory and Political Abandonment

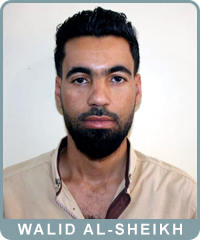

Walid Al-Sheikh

The issue of ISIS prisons and camps in northeast Syria remains one of the most complex and pressing security and humanitarian challenges in the region. Over time, it has become an overwhelming burden on the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), who have borne the responsibility of managing this file since the military defeat of the so-called ISIS “caliphate” in Baghuz in 2019. This responsibility—politically, economically, and militarily—has far exceeded their capacity. The recent statement by the Global Coalition in Madrid on June 2025 implicitly reaffirms this heavy responsibility and underscores the ongoing threat posed by the group, particularly through the unresolved issue of detainees held in facilities such as the aHol and Roj camps.

The SDF currently detains approximately 10,000 ISIS fighters in various prisons across northeast Syria, including around 2,000 foreign nationals (excluding Syrians and Iraqis). Additionally, over 50,000 individuals are held in Hol camp—mostly women and children—including more than 8,000 foreigners from nearly 60 countries. More than five years after ISIS’s collapse, no sustainable international mechanism has been established to either repatriate these individuals to their countries of origin or prosecute them before a recognized international judicial body.

The Hol camp, in particular, represents a multifaceted threat:

- An Ideological Incubator: The camp remains a fertile ground for the spread of extremist ideology, fueled by the presence of active hardline cells and the so-called “female hisbah” networks. Numerous assassination incidents have been recorded within the camp.

- A Global Security Gap: The continued presence of thousands of foreign nationals and their children poses a serious risk to international security, especially as many countries refuse to repatriate them or lack effective rehabilitation and reintegration programs.

- A Strain on Local Capacity: The AANES bears the full weight of this crisis without formal political recognition or direct international support, further weakening its ability to manage the situation effectively.

The Role of the SDF: The High Cost of Victory

The current situation cannot be understood without recognizing the central role played by the SDF in defeating ISIS. As the primary on-the-ground partner of the International Coalition, the SDF led some of the fiercest battles against the group in Raqqa, Deir Ezzor, and the Syrian desert. Following the military victory, the SDF assumed a critical and complex responsibility: guarding detention centers, managing camps, and countering sleeper cells—all while operating under limited resources and without formal international political recognition of the Autonomous Administration.

This responsibility poses a dual threat:

- Security Threat: Each prison break—such as the notorious 2022 escape attempt at Hasakah’s Sina’a prison—exposes the ongoing danger posed by ISIS and highlights the urgent need to strengthen local security infrastructure.

- Political Burden: The SDF continues to shoulder this burden without tangible political returns, while some regional and international actors exploit the detainee file as a political bargaining chip.

International Responsibility: The Need for a Strategic and Just Solution

Despite its reaffirmation of technical support and intelligence cooperation, the Madrid Declaration by the Global Coalition falls short of assuming meaningful responsibility for the detainee crisis. Warning of the persistent threat posed by ISIS without concrete action only serves to reproduce the danger rather than contain it.

A fair and strategic solution requires:

- Political and Financial Support for the AANES: Recognition of its role and granting it legal status to enter into international agreements—particularly those related to human rights and counterterrorism.

- The Establishment of an International Tribunal in Northeast Syria: To prosecute ISIS members within a legitimate legal framework, addressing the current legal vacuum.

- A Global Rehabilitation and Reintegration Program: Especially for women and children, coordinated in partnership with United Nations agencies and relevant humanitarian actors.

- A Comprehensive Repatriation or Resettlement Plan: Targeting citizens of European and Asian countries, accompanied by follow-up security measures and psychological rehabilitation.

The Future of ISIS Detainees

Without decisive, long-term solutions, the current situation risks catastrophic consequences:

- Prisons may evolve into a “mini-Guantanamo,” fueling resentment and radicalization.

- The likelihood of coordinated prison breaks by ISIS cells or external actors increases.

- A new generation is growing up in camps, absorbing extremist ideology in the absence of educational or social alternatives.

Given the complex challenges facing northeast Syria in the aftermath of ISIS’s defeat, it is no longer possible to separate the security and human rights dimensions of the crisis from the broader political and judicial imperatives of the transitional period. Between the prisons and camps left in ISIS’s wake, the social fragmentation it caused, and the sacrifices of local forces—chief among them the SDF, which lost thousands of fighters in what was not merely a local struggle but a global fight against terrorism—the urgent need for a comprehensive transitional justice framework becomes clear. Such a framework must honor sacrifices, guarantee rights, and lay the foundation for a durable and just political solution—especially as international efforts move toward restructuring the coalition and ensuring ISIS’s permanent defeat.

The Resurgence of ISIS: From the Syrian Desert to Major Cities

By early 2025, ISIS began to re-emerge as a growing threat amid a worsening security vacuum in the Syrian Badia and its surrounding areas. Multiple field and intelligence reports have confirmed renewed activity by ISIS cells across a wide area stretching from the border triangle of Deir Ezzor, Raqqa, and Homs, to the eastern countryside of Aleppo and Damascus. The group’s mobility across this vast desert terrain highlights both its tactical adaptability and the alarming lack of coordination between the various forces in control across Syria.

This dangerous development is a stark reminder of the conditions that preceded ISIS’s rapid rise in 2014—conditions marked by localized conflicts, political marginalization, and social exclusion. Today, ISIS cells are once again capable of launching swift, coordinated attacks on Syrian army and SDF positions, and in some cases, they operate near civilian centers without triggering an effective or timely security response. These indicators underscore a critical reality: the military defeat of ISIS was not the end of the threat—it was merely a temporary checkpoint. Continued neglect of comprehensive solutions in both the liberated northeast and the Badia could soon give way to a new wave of violence, this time alarmingly closer to urban centers such as Homs, eastern Hama, and the desert outskirts of Damascus.

As such, integrating transitional justice and the reintegration of local security institutions into Syria’s broader national counterterrorism strategy is no longer a political option—it is a strategic necessity dictated by shifting realities on the ground. Failure to seize this opportunity may not only derail stabilization efforts but could also lead to a repeat of catastrophe, this time at the heart of cities that once believed they had moved beyond the danger.

The Fallen in the Battle to Defend Humanity

The SDF fought a multi-layered war against ISIS, carrying the burden of direct combat alongside post-liberation security, administrative, and humanitarian responsibilities—without the protection of any formal legal or political international mandate. Despite sacrificing over 13,000 fighters and sustaining more than 25,000 injuries, these immense sacrifices have yet to translate into a meaningful role in any national or international political process.

The SDF’s management of ISIS detainees, prisons, and camps should not be viewed as an imposed obligation on a local actor, but rather as a legitimate demonstration of its foundational role in Syria’s future. This role must serve as the basis for full representation in any political dialogue with the Damascus government or within any international framework concerned with the country’s future.

Transitional Justice as the Cornerstone of a Sustainable Solution

Adopting a genuine transitional justice process in northeast Syria is essential to achieving long-term stability and preventing the resurgence of violence and extremism. This process must address several key dimensions:

- Accountability and Justice: Through the establishment of an internationally or locally recognized tribunal to prosecute ISIS members, and the creation of mechanisms to hold all perpetrators of violations accountable—including those responsible for systematic abuses in Afrin, Ras al-Ain (Sere Kaniye), and Tel Abyad.

- Memory Preservation and Documentation: Documenting ISIS’s crimes against diverse communities—Kurds, Arabs, Yazidis, Syriacs, and others—and embedding the collective memory of victims of terrorism and Turkish-backed factional abuses into public consciousness.

- Restoration of Rights: Ensuring the right of displaced people from Afrin, Ras al-Ain, and Tel Abyad to return to their homes, reclaim their property, and pursue legal pathways to restore stolen rights.

- Recognition of Sacrifice: Incorporating the memory of SDF martyrs into the narrative of the future Syrian state, and guaranteeing their families full legal and social rights in any future national charter or legal framework.

Negotiating with Damascus on New Foundations: From a Security Logic to a Rights-Based Approach

Any future negotiations with the Damascus government cannot be built on the premise of self-erasure or a return to the centralized model of governance that originally contributed to the rise of ISIS and the spread of chaos. Instead, such dialogue must be grounded in the following realities:

- The SDF is not merely a military actor, but a liberation force and a deeply rooted local security institution.

- The AANES now functions as a de facto governing authority, carrying out the responsibilities of a state—its inclusion in any political settlement must be viewed as a prerequisite, not a negotiable option.

- Political—not just administrative—decentralization is essential for the survival and stability of the Syrian state. It reflects both a practical necessity and a popular demand across the regions of northern and eastern Syria.

The Security Trauma of Local Communities

One of the deepest psychological and social barriers to rebuilding trust in the Syrian state among residents of northeast Syria is the entrenched sense of insecurity, shaped by years of war and embodied in several painful truths:

- The existential fight against ISIS: Hundreds of towns and villages paid a high price in blood to resist ISIS. Many residents feel that the central state abandoned them, while the SDF filled the vacuum and provided protection.

- Absence of guarantees from Damascus: The Syrian government has shown no willingness to acknowledge the AANES or the rights of local communities—casting doubt on the sincerity of any proposed settlement and raising fears of renewed authoritarianism.

- Experiences of displacement and abuse in Afrin, Ras al-Ain, and Tel Abyad: Hundreds of thousands remain displaced due to demographic engineering and forced displacement, all amid the silence of the Syrian government—fueling deep suspicion about the return of centralized rule without accountability or safeguards.

The issue of ISIS prisons cannot be managed solely through a narrow security lens. Instead, it must serve as a gateway to a broader, integrated political solution, one that includes:

- Holding the international community accountable for its legal obligations regarding the prosecution and repatriation of foreign ISIS fighters.

- Adopting a comprehensive transitional justice framework that begins with prosecuting ISIS and extends to redressing the full range of wartime injustices.

- Recognizing the SDF as a legitimate political stakeholder in any future political arrangement—not merely as a convenient security apparatus.

In the coming phase, there can be no talk of a genuine defeat of ISIS or sustainable peace in Syria without ensuring justice—both for the victims of terrorism and for those who suffered at the hands of the state. The sacrifices made by the SDF, the collective memory of communities targeted for extermination, and the unresolved file of detainees and camps must not be treated as peripheral technical issues. They constitute the very foundation of any future political or transitional justice process.

Acknowledging these realities is not an act of political charity—it is a strategic imperative to safeguard what remains of Syria and to prevent the war from resurfacing under new slogans or with even more devastating tools.

One cannot speak of a “lasting defeat of ISIS,” as asserted in the latest Coalition statement, without addressing the reality of the prison and camp crisis in northeastern Syria. The SDF and the AANES have shouldered a tremendous burden on behalf of the international community. Yet continued global failure to provide political recognition, institutional support, and a holistic solution renders the continuation of this mission nearly impossible.

What is urgently needed now is a genuine transitional justice process—one that includes fair accountability, a robust rehabilitation plan, and formal recognition of northeastern Syria’s central role in the global fight against terrorism. This region cannot afford to wait while the threat of ISIS is quietly recycled in the shadows.