Turkey in the Syrian Equation and Its Future

Modern Turkey, established in 1923 through the collaboration of the British, French, and Jewish triad following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the hands of the Committee of Union and Progress, served as a pathway toward the creation of the State of Israel in Palestine. It was the first Islamic country to recognize Israel, less than a year after its establishment, and the first Muslim president to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital was Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

The “Second Turkish Republic,” led by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) under Erdoğan, is viewed as a project sponsored by the British-American-Israeli alliance, created to serve their shared strategic agenda. The apparent disputes between Turkey and Israel over Middle Eastern issues are, in reality, disagreements over interests, shares, and spheres of influence. Erdoğan’s anti-Israel rhetoric and his seemingly pro-Arab, pro-Palestinian, and pro-Muslim statements are nothing more than propaganda meant to advance his neo-Ottoman ambitions in the region.

Turkey is the second-largest military power in NATO. Despite its active interference in the internal affairs of regional states—which highlights the extent of its influence—it remains the weakest link in the global system due to its internal fragility, stemming from its hostility toward the Kurds and its struggling economy. The republic, which was steered by the British at its founding toward waging war against the Kurds, now finds itself facing an even tighter and more dangerous impasse as it continues its anti-Kurdish policies, again under British direction and with the complicity of its American ally.

Statements and meetings conducted by U.S. President Donald Trump with several world leaders—especially in the Middle East—reflect the depth of U.S. interest in the region. This interest stems from the Middle East’s strategic importance in countering Chinese expansion, the new role of Israel following the events of October 7, its connection to the “Greater Middle East Project,” and Trump’s personal ambitions related to the Nobel Peace Prize. According to his statements, Trump sought to establish lasting peace in a region historically characterized by chronic crises—ushering in a post–Sykes-Picot era.

At the forefront of these crises lies the Gaza Strip. Trump presented a “peace map” consisting of several provisions, with the participation of Arab states and under the supervision of a committee chaired by former British Prime Minister Tony Blair—directly overseen by Trump himself. The same plan encompasses the Syrian, Lebanese, Iraqi, Iranian, and Turkish crises.

On the other hand, Erdoğan, after several attempts, managed to meet with the American president to present his demands concerning Syria—particularly regarding the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). However, the meeting did not unfold as Erdoğan had hoped. Trump reportedly accused him of being “unmatched in election fraud,” an implicit reference to the questionable legitimacy of Erdoğan’s rule in the eyes of Washington.

The issue of Syria was not discussed in depth, except for Trump’s remark that Erdoğan had fulfilled his “dream in Syria,” playing a major role in toppling the Assad regime, and that Turkey had gained control over Syria through its proxies—its mercenary armed factions. This statement can be interpreted as an indirect acknowledgment that Turkey bears responsibility for the atrocities and violations committed against various components of the Syrian people.

Turkey’s ambitions in Syria are undeniable. As a NATO ally of the United States, Ankara plays an indispensable role in the Syrian file. It sought to expand its military influence deep inside Syria and to bring the country under its orbit. Yet, these ambitions were met with strong Israeli opposition and airstrikes targeting the positions where Turkey attempted to establish military bases. Israel views Turkish expansion in Syria as a direct threat to its national security, fully aware that Turkish control over Syria’s political and military decision-making poses dangers no less serious than those of Iranian influence.

Nevertheless, given the deep economic, military, and security ties between Turkey and Israel, both Israel and the United States are likely to take Ankara’s role into consideration—granting Turkey a share of the Syrian “cake,” namely, the occupied territories in northern Syria. However, as always in international politics, nothing comes without a price.

The Russian–Ukrainian War

In a surprising and notable shift in stance, U.S. President Donald Trump stated that he believes Ukraine is capable of reclaiming all the territories seized by Russia—amounting to nearly one-fifth of Ukrainian land. This sudden change came after his failure to achieve peace in Ukraine, following earlier remarks suggesting that the war could be ended and peace achieved if Kyiv agreed to relinquish the areas occupied by Russia in eastern Ukraine.

However, judging by the current map of the Russian–Ukrainian conflict, the ability of the Ukrainian army to fully liberate its eastern territories from Russian occupation appears highly unlikely. Yet, such an outcome might still be possible if Ukraine’s armed forces receive sustained and substantial support from NATO, thereby altering the balance of power between the two sides and enabling Ukraine to regain parts of its occupied lands.

At the same time, Trump—despite his surprising statements that caught President Volodymyr Zelensky off guard—does not favor escalating military confrontation with Russia. Instead, he believes that cutting Moscow’s financial resources would be a more effective means of compelling it to return to the negotiating table.

The United States views Turkey as a potential game-changer in the Russian–Ukrainian war—either by providing military support to Kyiv or by halting its purchases of Russian oil and gas, thereby cutting off vital Russian revenue streams. Trump has been working to pressure Ankara into taking these steps, particularly after relations between Russia and Turkey deteriorated following the fall of the Assad regime in Syria and Moscow’s subsequent accusation that Ankara had “betrayed” it over the Syrian file.

Turkey can no longer continue its pragmatic policy of playing both sides—Russia and the West. Consequently, it will be compelled to realign with the Western bloc and implement its demands concerning Russia, including the imposition of sanctions and the suspension of Russian oil and gas imports.

Meanwhile, disputes between Baghdad and Erbil have been resolved, allowing the resumption of oil exports from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq through Turkish territory to the port of Ceyhan—a development that could serve as a substitute for Turkey’s potential halt in Russian oil purchases.

In addition, there is a possibility that the United States will lift certain sanctions on Turkey and revive pending deals such as the F-35 fighter jet program and other defense agreements that remain suspended between the two allies.

However, Ankara has its own demands concerning the Syrian situation—particularly regarding the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) and the SDF. Erdoğan continues to harbor ambitions of obtaining a green light for a large-scale military offensive against AANES-held areas, or at the very least, maintaining Syria’s centralized political system while integrating SDF fighters into the Syrian army as individual soldiers rather than as an independent military entity.

The Importance of Eastern Euphrates

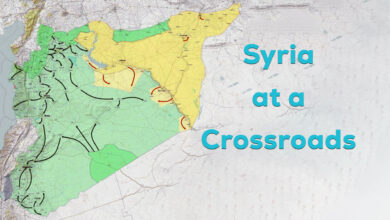

The region east of the Euphrates River—areas administered by the AANES—differs markedly from other parts of Syria due to its distinct geopolitical position, which enables it to play a significant role in shaping Syrian politics. It is considered Syria’s breadbasket; without it, the country cannot achieve food security. The area is also rich in natural resources, particularly oil and gas, which once generated enormous revenues for the former Syrian regime—revenues that were not even included in the state’s official budget.

Additionally, the region holds major trade routes connecting east and west, most notably the strategic M4 Highway. It also offers potential for linking oil and gas pipelines between Iraq and Syria, extending to the port of Baniyas and from there to Europe.

The area’s cultural and ethnic diversity, its connections with neighboring states, and the presence of a well-organized and experienced military force—a key partner of the Global Coalition in the fight against ISIS—all add to its strategic significance. Whoever controls these assets can effectively influence political decision-making in Damascus without necessarily having to penetrate deep into Syrian territory or seize the capital itself.

For Turkey, the significance of the AANES region is tied to two main factors:

1- Preventing Kurdish autonomy — blocking Syrian Kurds in Rojava (Western Kurdistan) from obtaining constitutional rights similar to those gained by the Kurds in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

2- Pursuing political leverage — after failing to extend its influence deep into Syria or dominate political decision-making in Damascus, Ankara now sees eastern Syria as an alternative gateway to controlling Syria’s political future, particularly in light of its ambitions tied to the so-called “Misak-ı Millî” (National Pact).

For these reasons, President Erdoğan has repeatedly sought U.S. approval to launch a military offensive against the AANES—similar to Turkey’s previous incursions in Afrin, Tel Abyad, and Ras al-Ain (Sere Kaniye). However, such attempts have been consistently rejected by both the United States and Israel.

The AANES in the Regional Balance of Power

The United States and Israel are fully aware of Erdoğan’s ambitions to dominate Syria’s political and military decision-making following the collapse of the Assad (Baathist) regime, and of his desire to assume the role previously played by Iran in Syria. Any new Turkish expansion would inevitably disrupt the existing balance in the country.

Both Washington and Tel Aviv have a shared agenda concerning Syria’s new political order—one reportedly centered around Ahmad al-Sharaa —amid speculation about the role assigned to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the possibility of it assuming authority in Damascus. This agenda may be linked not only to Syria’s internal restructuring but also to prospects for Syrian-Israeli normalization and, more broadly, to a regional vision influenced by Sunni Salafi thought.

Turkey’s emerging role in Syria could directly impact this agenda. For example, Ankara is one of the main obstacles to reaching a security agreement between the new Syrian leadership and Israel. Turkey exerts pressure on Damascus, preventing it from concluding any such deal without addressing Turkish concerns—particularly those related to the SDF, the AANES, the future system of governance in Syria, and even the drafting of a new constitution.

Having failed to establish a deep military presence inside Syria—through bases, intelligence centers, or direct control over political decisions in Damascus—Erdoğan has shifted his focus toward the eastern Euphrates. He has repeatedly issued threats and set deadlines for military action, even suggesting possible coordination with the new Syrian government should the SDF refuse to comply with Turkish demands.

For Ankara, eastern Syria represents a strategic substitute for the deeper Syrian heartland. It is also linked to the “Misak-ı Millî” vision of uniting both banks of the Euphrates under Turkish influence and connecting them to Turkish-controlled areas in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

If Turkey were to seize control of eastern Syria, it would gain leverage over Damascus by controlling the region’s vital natural resources—resources essential for the new Syrian government to consolidate its rule. In such a scenario, the east of the Euphrates would likely mirror the situation in the Turkish-occupied north, where Damascus would have little to no effective authority.

This outcome would pose a serious threat to Israel’s security and to the broader strategic objectives of the United States in the region.

In conclusion, the territories of the AANES constitute a geopolitical cornerstone within the Syrian equation—one that holds considerable weight in the calculations of all major regional and international actors involved.

The Status of the AANES Areas in the Syrian Equation

The continuation of the Syrian crisis, even after the fall of the Baath regime, remains closely tied to Turkey’s direct interference in Syria’s internal affairs. Diplomatic activity between Ankara and the new Syrian leadership has intensified, with both sides actively engaging over every decision or event related to the country’s internal situation. The new Syrian government remains under substantial Turkish influence and cannot make major decisions without Ankara’s approval.

Turkey is pressuring the new Syrian regime to include the territories of the Autonomous Administration in the Syrian-Israeli negotiations as a precondition for signing a security agreement or even normalizing relations with Israel. Under this arrangement, Israel would reportedly give the new Syrian army the green light—backed by Turkish support—to launch a military operation against the region.

As for Israel’s position, the situation in Suwayda differs from that of the Autonomous Administration areas in terms of Israeli involvement. There are no ties, relations, or Israeli support for the AANES or the SDF, nor any Israeli protection that could be traded away to the new Syrian regime. The SDF remains aligned with the U.S.-led Global Coalition, and Israel has no role in this relationship.

Therefore, any demands by the new Syrian government concerning the eastern Euphrates or the SDF carry little weight in negotiations, as these issues are directly linked to Washington and the Coalition.

Even if Turkey exploits its evolving role in the Russian–Ukrainian war and complies with U.S. requests, Washington is unlikely to bargain with Ankara over the fate of the AANES or the SDF for two main reasons:

- Ideological concerns — The new Syrian regime is rooted in jihadist Salafi ideology. Even if Ahmad al-Sharaa changes his appearance and adopts a more Western-friendly image, he and his armed factions—composed partly of foreign jihadists—remain listed as terrorists in Western perception.

- Israeli security — The U.S. cannot grant Turkey significant leverage that might threaten Israel, especially given the geopolitical importance of the AANES areas.

Moreover, the SDF maintains an independent command structure distinct from other armed groups in Syria—many of which depend on the AANES territories for survival and protection. The SDF defends these areas and their populations from Turkish-backed mercenaries, the new Syrian army, and internal security forces, all of which have recently built a record of violations and atrocities.

Hence, Turkish movements and claims of receiving a “green light” for action largely remain within the realm of speculation—part of Ankara’s ongoing pressure campaign on both the United States and Israel.

Has Turkey Achieved Its Dream of Controlling Syria?

The U.S. president’s statement that “Turkey has achieved its dream of controlling Syria” likely does not refer to the entire Syrian geography. It more plausibly pertains to the Turkish-occupied northern regions. Erdoğan effectively controls northern Syria, where Damascus holds no authority, and continues to consolidate his military presence through multiple bases and posts—such as his recent control of Kuweires Airbase, now turned into a Turkish military facility. He also continues the demographic engineering project initiated by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1925 under the “Eastern Reform Law,” aimed at displacing the region’s original inhabitants, particularly Kurds—and in some cases Arab communities—to pave the way for integration into Turkish provinces.

Alternatively, Trump’s statement may have been a veiled way of granting Erdoğan an indirect green light to launch an operation against the SDF—not to dismantle the AANES or the SDF, as Erdoğan assumes, but rather to draw Turkey deeper into entanglement, much like what happened with the new Syrian regime in Suwayda. There, Ahmad al-Shar’a and his government believed they had received Israel’s approval, only to face devastating consequences following the massacres carried out by the General Security forces, the Syrian army, and so-called “tribal mobilizations.” These events ultimately pushed Suwayda closer toward establishing an autonomous administration in southern Syria.

Thus, the AANES and its military arm, the SDF, have become an undeniable reality in the Syrian equation. However, this does not mean that AANES-held territories are immune to potential military aggression—whether from Turkey and its proxies or from the new Syrian regime itself.

If such an assault were to occur, it would likely aim at securing specific strategic gains—such as control over the Tishrin Dam and Lake Assad (for water and electricity) or eastern Deir ez-Zor’s oil and gas fields.

Russia’s military presence could also play a decisive role in this context. Moscow’s influence in Syria has significantly diminished, now limited mainly to its bases in Khmeimim, Tartus Port, and Qamishli Airport. Despite its continued relevance for both the U.S. and Israel—especially amid Turkish ambitions along the Syrian coast—Turkey’s potential expansion east of the Euphrates could threaten Russia’s remaining foothold, particularly as relations between Ankara and Moscow deteriorate and Washington seeks to pull Turkey back into the Western camp.

In the event of a Turkish-led attack on the AANES territories, Russia may choose to side with the SDF and support the establishment of an autonomous administration along the Syrian coast as a means of preserving its military presence in the country.

It is likely that the recent visit of General Ali al-Nuasan, the Chief of Staff in Ahmad al-Sharaa’s government, to Moscow aimed to provide guarantees to Russia in exchange for its neutrality—or at least to ensure it would not side with the SDF in case of conflict.

Ultimately, the “victories” achieved by Middle Eastern regimes—whether domestically or regionally—under authoritarian and nationalist systems are temporary and serve Western interests above all. History has repeatedly proven that such triumphs soon collapse into setbacks that destabilize these regimes from within. This pattern is evident in the Palestinian cause, Iran’s regional expansion, the downfall of both the old and new Syrian regimes, and other crises across the region. The cycle of setbacks continues—and soon, it may reach the Turkish state itself.

The Future of Syria under the Current Circumstances

Syria’s future is shaped by several interrelated factors—domestic, regional, and international. Domestically, it depends on the policies adopted by the new regime; regionally, it is closely tied to Israel, which seeks to secure an arrangement that serves its strategic interests. This includes an Israeli–Syrian security agreement recognizing Israel’s sovereignty over the occupied Golan Heights, maintaining control over key strategic positions such as Mount Hermon, establishing a de facto buffer zone—particularly in the governorate of Suwayda—and ultimately bringing Syria into Israel’s geopolitical orbit.

Turkey is another influential regional actor, whose role will be discussed further below. Internationally, Syria’s trajectory is also directly linked to the United States’ strategic posture in Syria and the broader Middle East.

First, current U.S. policy is based on avoiding direct military involvement in conflicts, instead relying on local partners and air power to confront its adversaries.

Second, it is essential to distinguish between the various local military forces in Syria according to their legitimacy and role. The SDF, partners of the Global Coalition in the fight against ISIS, differ fundamentally from Turkey’s proxy militias—many of whom are composed of former ISIS members and led by individuals designated as terrorists—and from the so-called “New Syrian Army,” which includes fighters from HTS and other foreign jihadists. According to U.S. President Donald Trump, these groups act as Erdoğan’s agents in Syria.

Therefore, it is only natural that the international community continues to rely on a capable and disciplined force such as the SDF, whose organization, experience, and military readiness make it a cornerstone of stability and security in Syria and the wider region—a fact increasingly recognized by the global community.

Despite existing tensions between the SDF and Damascus, Turkish interference in Syria’s internal affairs—backed by Qatar—risks complicating ongoing negotiations and could spark renewed internal conflict, which regional powers like Israel and Turkey may exploit to their advantage in the short term.

Recent developments around Deir Hafer and the Tishrin Dam clearly indicate a growing trend toward military escalation by the new Syrian regime and Turkey, particularly following the return of Erdoğan and Ahmad al-Sharaa from New York. Both appear to believe they have received a green light from the United States.

In reality, however, the presence of two dominant spheres of influence in Syria—Turkish and Israeli—will inevitably lead to friction between them, compounded by the resurgence of jihadist ideology in the country. Consequently, Turkish influence in Syria may decline, much like that of Iran, as it remains constrained by Israel’s security interests—a shift tied to the peace process initiated by Abdullah Öcalan.

Given the exclusionary policies pursued by the new regime toward Syria’s diverse communities, and the repercussions of these policies in both the coastal and southern regions, Syria appears to be heading toward a decentralized system of governance. The SDF, meanwhile, are likely to remain an independent military power even if formally integrated into the Syrian army, especially as ISIS cells continue to reemerge and expand their operations under the new regime.

Turkey and Its Chances of Surviving the Greater Middle East Project

In Volume V, page 492 (Arabic version), the Kurdish thinker Abdullah Öcalan asserts that the first Turkish Republic (the secular nationalist CHP Republic) was, in essence, the path that led to the creation of Israel during the 1920s. By the early 2000s, the second Republic (the AKP) was established under the triad of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Israel, with the aim of channeling Islamic radicalism into a “moderate Islamic republic.” This project sought to neutralize Iranian and Arab nationalism as potential threats to Israel, to contain both Iranian Shiite fundamentalism and Arab radical Islamism, and to integrate them—along with Arab secular nationalism—into the existing global hegemonic system.

Although Turkey remains the weakest link in this system, largely due to its failure to resolve the Kurdish question, its strength lies in its capacity to revive the historical alliances that characterized the early Republic during the War of Independence—this time, on the foundation of a democratic nation. However, the entrenched chauvinistic and racist mindset has dismantled those bonds and severed the centuries-old Kurdish–Turkish partnership. Efforts to assimilate the Kurds, suppress their identity, and eliminate their cause through countless military operations have all failed—especially following the emergence of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has proven resilient against every attempt to defeat it.

Despite the PKK’s repeated initiatives to reach a peace agreement with the Turkish state—both in the 1990s and the 2010s, including Öcalan’s own peace proposal aimed at ending the armed conflict—Turkey’s racist nationalism and Turanist fascism have rendered peace a distant prospect.

Turkey fully understands the implications of the Greater Middle East Project (GMEP) and recognizes that it is not exempt from it, even as an active participant. As President Erdoğan himself once admitted, Turkey functions not as a dominant power but as a pawn in the hands of the West, executing Western agendas in the region. This realization prompted Devlet Bahçeli, leader of the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), in the wake of the October 7 events and Israel’s growing role, to revisit the notion of Kurdish–Turkish brotherhood, calling for an end to the armed conflict and peace talks through Abdullah Öcalan.

Turkish leadership, particularly Bahçeli, is aware of the historical power of Kurdish–Turkish solidarity, which once stood firm against external agendas—most notably during the War of Independence (1919–1922), and earlier in key battles such as Manzikert (1071), Chaldiran (1514), Marj Dabiq (1516), and al-Raydaniyah (1517). Yet, by betraying this brotherhood, denying Kurdish existence, glorifying Turkish nationalism, and resorting to violence and forced assimilation, Turkey has weakened itself from within and made it increasingly vulnerable to Western manipulation.

Öcalan’s peace initiative, rooted in Kurdish–Turkish and Kurdish–Arab brotherhood and the philosophy of the democratic, pluralistic society, offers a genuine framework for stability and regional peace—one that could spare the Middle East from endless bloodshed, atrocities, and wars.

The Middle Eastern regimes’ own policies—oppressing their peoples, suppressing democracy, and clinging to the centralized systems imposed by the British–French–Zionist triad in the early 20th century—have only given Western powers justification to intervene under the pretext of “promoting democracy.”

Öcalan’s initiative, however, requires patriotic Turkish leaders capable of making bold, historic decisions that serve their peoples rather than the Western agenda. Yet, Turkey continues to play a key role in advancing Western interests, particularly in Syria, where it obstructs democratic transformation and fuels crises that will ultimately rebound against it.

Turkey’s policies of denial and assimilation will not succeed in ending the Kurdish question. Its continued intransigence—refusing peace and hoping for political or military shifts to reinforce its racist policies—will only deepen its crisis. When Turkey finally finds itself engulfed by the turmoil it helped create, the West will have already made its decision regarding its fate.

As noted by U.S. envoy Thomas Barrack, the Middle Eastern states were founded as tribal and clan-based structures by Britain and France in the early 20th century—essentially an extension of the Sykes–Picot Agreement. This framework implies the future establishment of decentralized systems within these countries, ostensibly to grant local populations constitutional rights.

Had the region’s own regimes undertaken this democratic transformation, the Middle East’s destiny would have been profoundly different, placing it in a strong and dignified position on the global stage. Instead, fascist and racist regimes, implanted by Western powers, became the cause of the region’s enduring conflicts—mere tools for Western domination. As their utility declines, these regimes will begin to collapse like dominoes; centralized authoritarian states can no longer adapt to the new international order and have become burdens rather than assets.

Those who created them must now dismantle them and establish new systems—something already underway with the collapse of the Iraqi, Libyan, Yemeni, Tunisian, and Egyptian regimes. Following October 7, a new phase has begun, centered on Israel, extending through Hamas, Hezbollah, the fall of the Baath regime in Syria, and the curbing of Iranian influence, before continuing in Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, and eventually Turkey.

Turkey remains a principal instrument within this project. Its fascist policies and neo-Ottoman ambitions make it a key executor of the Western plan. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its leader Erdoğan were shaped by the U.S.–U.K.–Israeli triad. Turkey’s role will end when the time comes—likely in conjunction with the neutralization of Iran and its removal from the regional equation.

For over two decades, Ankara’s interventionist foreign policy, which it has framed as victory, will eventually backfire, leading to Turkey’s fragmentation, just as other regional states have been dismantled. Despite NATO membership, Turkey will remain, in the eyes of the West, an untrustworthy, expendable state—to be weakened or even dismembered to ensure that Israel remains the central power in the Middle East, with all other nations revolving within its orbit.

Unless Turkey seizes this last historical opportunity to restore Kurdish–Turkish brotherhood and implement the desired democratic transformation—a reform that would strengthen rather than weaken the state—it risks losing its standing altogether.

In conclusion, all previous Turkish agreements with Iran, Syria, and Iraq aimed at suppressing or eliminating the Kurdish issue pose, paradoxically, a strategic threat to Israel, even when their stated purpose was merely to oppose Kurdish aspirations. Turkey seeks to enhance its leverage with the U.S.–U.K.–Israeli alliance, yet it cannot achieve this due to the very global structures and policies that have shaped it over the past two centuries.

Thus, Turkey must either submit to the global order or face the consequences of its actions, as happened with Iran and Iraq. Full compliance would require reconciliation with the Kurds and a recalibration of relations with Syria and Iran. Should Ankara refuse and instead seek new alliances, it must be prepared for a sweeping campaign similar to Iraq’s fate.

Ultimately, Turkey’s survival depends on resolving the Kurdish issue through democratic, peaceful, and open means, granting autonomy at minimum, and reviving a genuine alliance reminiscent of the national liberation era (1923) and the great battles of Manzikert (1071), Chaldiran (1514), and Marj Dabiq (1516). Only through such transformation can Turkey evolve from a subordinate state within the hegemonic global order into a powerful regional actor, capable of standing as an independent global force against the dominance of Israel, the United States, and the United Kingdom.