Turkish Influence in Northern Syria

Turkey is considered one of the most interventionist regional powers in the Middle East in general, and in Syria in particular, due to Syria’s strategic importance for Ankara and its broader expansionist ambitions in the region. Before World War II, Turkey succeeded—through an agreement with France—in annexing the Syrian province of Alexandretta (Iskenderun). Today, it seeks to assert control over Syria through its proxy forces and its influence over the new authorities in Damascus.

After failing to implement its early plans in Syria—overthrowing the former regime at the start of the crisis and transforming the country into an Ottoman-style province under the Muslim Brotherhood—Turkey shifted its focus to northern Syria. It began taking steps to detach the region from Syria proper, starting with the occupation of Jarablus, al-Bab, and Azaz following the defeat of its affiliated terrorist organization, ISIS, by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). This was followed by the occupation of Afrin in 2018, and Tel Abyad (Gire Spi) and Ras al-Ain (Sere Kaniye) in 2019, alongside repeated attempts to pressure the United States to withdraw from east of the Euphrates and grant Ankara a green light to launch attacks against the areas of the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES).

After failing during the former regime to amend the Adana Agreement or to weaken the DAANES in exchange for normalization, Erdoğan’s Turkey now sees new opportunities. With the fall of the old regime and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) assuming control in Damascus—a group over which Turkey wields significant influence—Ankara believes it can now realize its plans in Syria.

Turkey’s Ambitions in Syria

Following the rise of political Islam under Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its assignment within the “Greater Middle East Project” by the global system—whose goals included transforming Turkey from a secular to an Islamic state—Erdoğan’s ambitions became clear: restoring Ottoman glory and exploiting Middle Eastern crises, including through the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria. However, these ambitions were gradually narrowed to northern Syria due to changes in the political and military balance after Russia’s direct intervention in Syria in 2015 and subsequent international arrangements that rewarded Erdoğan with control over Afrin, and later Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain. Ankara now seeks to launch further attacks against the DAANES under pretexts unrelated to its actual security (claims of national security, preserving Syria’s unity, countering separatism, or the SDF’s non-integration into the new Syrian army) in order to expand its influence and consolidate its presence in northern Syria, pursuing the Ottoman-era Misak-ı Millî (National Pact) goal of controlling all of northern Syria.

From this expansionist Ottoman perspective, Turkey views northern Syria as part of its historical domain, linking it to the National Pact, which also encompassed southern Kurdistan (northern Iraq, including Mosul and Kirkuk). Through the modern Turkish state, Ankara seeks by all means to control what remains of this region—the DAANES areas—although it has yet to obtain U.S. approval.

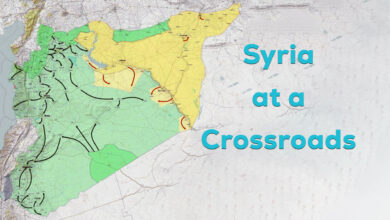

Except for the DAANES territories, which aim to rebuild Syria as a unified, democratic state, the country remains divided between HTS (the new authority in Damascus) and Turkish-backed mercenaries in the occupied north. Damascus has no real authority over northern Syria or Idlib, HTS’s former stronghold. Turkish-backed factions—including Amshat, Hamzat, Ahrar al-Sharqiya, the al-Jabha al-Shamiyah, and remnants of the former “Syrian National Army (SNA)”—do not answer to interim president Ahmad al-Sharaa or the Syrian Ministry of Defense. Even those nominally integrated into the new Syrian army remain under Turkish command.

Effectively, according to current military maps and areas under transitional government control, Syria is divided into two zones: The Turkish-occupied north (Aleppo, Idlib, Tel Abyad, and Ras al-Ain), under the control of Turkish-backed mercenaries and Turkey itself, which has established military bases there; and the remaining territories, excluding Suwayda, under Damascus authority.

Given ongoing regional interference in Syrian affairs, Ahmad al-Sharaa seeks a pragmatic policy toward regional and international powers to preserve his authority. However, heavy international pressures—from the U.S., Europe, and Israel—limit the extent to which he can pursue such pragmatism. Turkish influence over the new Syrian authorities, combined with Ankara’s agenda clashing with Western interests, has prevented the government from making independent national decisions. In comparison, Western pressures—linked to sanctions, legitimacy, or political backing in Damascus—currently outweigh Turkish influence, meaning tensions between Ankara and Damascus could resurface if Turkish interests in Syria begin to decline.

Turkey’s Policy in Syria

Turkey pursues a policy of double standards in Syria. On one hand, it calls on Israel not to intervene in Syrian affairs and demands the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the territories it occupies in the south. On the other hand, Turkey itself intervenes in Syria, preventing Damascus from reasserting control over northern Syria. Ankara insists that the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) be integrated into the Syrian army as individual members rather than as an organized military unit, thereby stripping the region of its military capacity and facilitating Turkish control. Turkey also seeks to dismantle the DAANES, which represents a democratic model in Syria, and demands amendments to the Adana Agreement to serve its own ambitions, including expanding the security zone from 5 km to 35 km to legitimize its intervention in northern Syria before any unexpected political changes occur.

Turkey has also actively obstructed negotiations and prevented any formal agreement between the SDF and Damascus. General Mazloum Abdi’s visit to Damascus, under U.S. auspices, aimed to bridge divisions, limit Turkish interference, and discuss the rebuilding of the Syrian army. However, these talks resulted only in a verbal agreement rather than a formal, written accord similar to the March 10 agreement. This outcome can be seen as a mechanism used by the Damascus authorities both to evade binding commitments and to avoid angering Turkey. The subsequent visit of Foreign Minister al-Shaibani to Ankara immediately after the meeting was intended to brief Turkey on the U.S.-mediated discussions in Damascus and to receive instructions on how to implement the verbal agreement regarding the SDF.

Occupied Northern Syria

The occupied areas of northern Syria—under the control of Turkish-backed mercenaries, including the northern countryside of Aleppo (Jarablus, al-Bab, and Azaz), Afrin, and Tal Abyad (Gire Spi) and Ras al-Ain (Sere Kaniye)—are effectively independent from Damascus. These areas are managed separately from the central government, despite attempts by the new Syrian authorities to assert control. All such attempts have failed due to Turkish pressure, which prevents Damascus from reestablishing authority over these territories.

The region is dominated by Turkish-supported factions, including the Hamzat, Amshat, Ahrar al-Sharqiya, al-Jabha al-Shamiyah, and Sultan Murad groups. Some of these fighters have nominally joined the new Syrian army, but they remain under Turkish command, not answering to interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa. Through these proxies, Turkey maintains substantial influence over occupied northern Syria.

Strengthening Turkish Influence in the North

Turkey’s current policy focuses on consolidating its presence in northern Syria. Ankara regards this region as a core zone of Turkish influence, reinforced by the international community’s disregard for the demographic changes Turkey is implementing and the establishment of Turkish military bases and outposts on Syrian soil. Turkey is steadily advancing plans to separate northern Syria from Damascus by continuing its demographic engineering, preventing the return of displaced residents of Afrin—even if verbal agreements exist between General Mazloum Abdi and Ahmad al-Sharaa regarding their return—and supporting its proxies by integrating them into the new Syrian army. For example, the mercenary Abu Amsha was appointed commander of the 25th Division in Hama, and Abu Hatem Shaqra was appointed commander of the 86th Division in eastern Syria.

These appointments by the new Syrian Ministry of Defense raise concerns: both commanders have a history of human rights violations, ties to ISIS, and are on U.S. sanctions lists. However, the appointments may reflect Turkish pressure to expand its influence in Syria. This expansion risks potential confrontation with Israel, which, having previously removed Iranian influence from Syria, now faces the growing Turkish presence—a threat considered comparable to that posed by Iran. Turkey has a long history of connections with terrorist groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood, ISIS, and various jihadist organizations from Chechnya, Xinjiang, and elsewhere, along with its mercenary proxies. Israel has acted to limit Turkish influence in Syria, including targeting military bases in Palmyra that Turkey sought to convert into Turkish outposts after visits by Turkish military advisors.

After setbacks against Israel in central Syria, Turkey has increased pressure, violated ceasefire agreements between the SDF and Damascus through its proxies, and sent threats to the Autonomous Administration and SDF-controlled areas. Ankara aims to extend its influence east of the Euphrates and control oil-rich areas, especially in Deir Ezzor, via mercenary groups like Ahrar al-Sharqiya or the 86th Division under Abu Hatem Shaqra, should a military campaign against the Autonomous Administration occur.

Turkey’s strategy indirectly seeks to detach northern Syria by preventing the restoration of Syrian sovereignty, including over Idlib, supporting proxy factions that form the backbone of its demographic and military control, and maintaining military bases to secure dominance. It also aims to preserve Syria’s centralized system of governance, which serves Ankara’s interests, while undermining the DAANES through violent campaigns, as seen in Afrin, Tel Abyad, and Ras al-Ain, as a precursor to annexing occupied areas.

Following its setbacks in central Syria against Israel, Turkey now seeks to maintain and expand its northern influence, potentially extending into the DAANES territories, which lack Israeli protection, like Suwayda. Ankara appears confident it can negotiate with the United States to obtain a green light for a military invasion. Yet, despite being an ally of the U.S., Israel, and Western states, Turkey remains an unreliable actor whose deviations from agreed strategies pose a direct threat to the regional interests and policies of these powers.

Ending Turkish Influence

Armed factions of various kinds pose a long-term threat not only to the United States, Russia, China, and Israel but also to some Arab states. They cannot be fully trusted as long as they act as proxies for Turkey in Syria, advancing Turkish influence and its associated ideological agenda. As the new Syrian government seeks international legitimacy, consolidates power, and aims to control the entire Syrian territory, it may attempt to weaken the influence of these factions (mercenaries) with support from Western, Russian, Israeli, and even domestic actors.

Interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa is currently striving to solidify his rule and have his name removed from UN sanctions lists. China and Russia, however, oppose delisting al-Sharaa (formerly Abu Mohammed al-Jolani) due to the presence of foreign fighters under his authority, including Uyghurs, Chechens, Uzbeks, and other related jihadist groups. Because al-Sharaa and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (the interim government) remain under Turkish influence, decisions made under external pressure negatively impact his governance. He lacks full control over the newly formed Syrian army, which was structured weakly under regional pressure and includes factions—mercenaries, jihadists, and foreign fighters—with external agendas, as well as uncontrollable groups. This presents a serious threat to al-Sharaa’s authority in the event of shifts in the Syrian file.

Conflicting pressures further complicate matters. U.S. and Israeli demands for stability in Syria often conflict with Turkish pressure to launch military operations against the SDF. The imbalance of power between the U.S., the West, and Israel on one side and Turkey on the other strengthens Western influence over Turkish influence, leading to potential disputes between Ankara and Damascus. Although al-Sharaa currently pursues a pragmatic policy toward the countries involved in the Syrian issue, this approach weakens his authority.

A hidden struggle exists among regional and international powers—Turkey, Israel, Russia, and the U.S.—over Syria. Despite controlling northern Syria, Turkey is the weakest link due to internal and external constraints. Israel has successfully limited Turkish advances into central Syria, Russian forces along the coast constrain Turkey’s expansion, and the U.S. refuses to greenlight Turkish military operations against the DAANES areas. Turkish-backed mercenaries are on U.S. sanctions lists and represent a future threat to the new Syrian government, being outside state control. Given ongoing changes in the Middle East (the “Greater Middle East” project) and Israel’s prominent role in preventing any central state from threatening its ambitions, Turkey’s influence remains constrained.

The new Syrian government, seeking to restore order in occupied northern Syria and reestablish security, military, and economic stability, lacks a disciplined military force to defeat rogue groups and reunify Syria under its authority. If negotiations between the SDF and the new Syrian government proceed positively, restructuring the Syrian army and creating a core force aligned with national interests may become possible. This could rely on the SDF, which includes military councils from most Syrian regions, to combat terrorism, purge northern Syria of Turkish proxies, and reintegrate these areas into Syrian governance. Western pressure on al-Sharaa to protect minority rights, fight terrorism, and promote democracy in Syria would further weaken Turkish influence.

Turkish influence depends on the degree of political and military independence in Damascus, which affects Syrian sovereignty. One key reason for the fall of the former Assad regime was its inability to break free from Iranian control, which dominated all state institutions politically, militarily, and economically—a challenge that could similarly affect the new Syrian authorities regarding growing Turkish influence. Al-Sharaa is attempting to balance the interests of countries involved in the Syrian crisis without violating their red lines—a complex task given conflicting agendas among allies such as Turkey, Israel, and the U.S., alongside Russian presence and Syria’s economic deterioration.

Nevertheless, the peace process initiated by Abdullah Öcalan from prison in Imrali, Turkey, is expected to impact Turkish foreign policy and its regional ambitions. Democratic reforms in Turkey and positive regional effects could significantly reduce and potentially resolve Middle Eastern crises. Turkey’s approach to this peace initiative, following substantial steps by the PKK, including the withdrawal of its fighters from Turkish territory, will shape Turkey’s future as a regional power in the Middle East and provide a sustainable response to ongoing regional transformations (the Greater Middle East project). Success could have positive repercussions for Turkey domestically, on the Syrian issue, and on its broader regional interests. Conversely, failure could plunge Turkey into civil conflicts and economic crises, undermining its regional standing to the benefit of other regional and international powers.