A Political-Analytical Reading of Middle Eastern Transformations Following the Fall of the Syrian Regime

Introduction:

In attempting to read the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East, one can observe beyond any doubt that the old balances which governed the region for an entire century are now collapsing and disintegrating. The instruments of capitalist modernity, in their various forms, are being recycled and reassigned in ways that serve the needs of the global order and the redrawing of spheres of influence. This process unfolds alongside serious efforts to address the deepening structural crises afflicting Middle Eastern regimes on the one hand, and attempts to entrench dominance over the peoples of the region on the other.

Within this complex context, profound reflective questions are intensifying regarding the nature of the historical impasse confronting the region. This recalls the words of the German thinker Theodor Adorno (1903–1969), who famously stated, “Wrong life cannot be lived rightly,” a phrase that underscores the impossibility of constructing sound solutions upon a flawed, distorted, or unhealthy political structure.

Accordingly, the first step toward any viable project of resolution must begin with an accurate diagnosis of the region’s condition: analyzing the elements of historical blockage, identifying the loci of structural dysfunction, and orienting the compass in the correct direction before embarking on any new process of construction. The more accurate the diagnosis, the clearer the nature of the crisis or ailment becomes, and the more solid, realistic, and acceptable the starting point for a solution will be. Hence, it becomes essential that in this reading we remain clear in our objectives, realistic in our reflective questions and in our intellectual, political, and social visions, and more flexible in the means of achieving these visions especially in light of the rapid transformations sweeping the region as a whole, and the collapse of patterns and forms of control that had long appeared firmly entrenched.

Chronology of Transformations in the Region

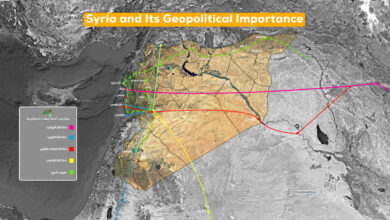

With the dawn of the twentieth century, and amid the formation of the modern Middle East, two principal objectives emerged for the major colonial powers (Britain and France):

First: the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire and the distribution of its legacy through the creation of weak, manageable, and controllable nation-states.

Second: the establishment of a Jewish state “the Promised Land” in Palestine, intended to become the dominant power in the Middle East in the future. On this basis, maps of influence were designed and regional relationships were arranged in ways that facilitated the continued dominance of Western capital.

When the leader of the socialist “October Revolution,” Vladimir Lenin (1871–1924), revealed the Sykes–Picot Agreement following the Bolshevik victory in 1917, a large part of the scheme that had led to the First World War was laid bare: a struggle among powers over the Middle East—its wealth and its strategic location—for all parties involved.

After Tsarist Russia withdrew from the war, the Kemalist movement in Turkey, led by Mustafa Kemal “Atatürk,” moved quickly to fill the vacuum in Anatolia. It benefited from direct support provided at the time by the Soviet Revolution, as well as from the fragmentation of Kurdish forces, which had not yet reached a unified organizational form (despite repeated attempts to articulate themselves as a people with a cause that required resolution, in line with the demands of an oppressed people seeking their rights). With the Kemalist movement’s victory in its war against Greece, the implementation of the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres—along with its explicit recognition of Kurdish national political rights (Articles 61, 62, and 63)—became impossible. Western powers replaced it with the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), which consolidated the emergence of modern Turkey as a centralized state with a rigidly nationalist (fascist) character.

From that point onward, Turkey was assigned two strategic missions in the Middle East:

- Safeguarding Western interests and preparing the environment for the future establishment of Israel. Turkey presented itself as a model of nationalist modernity aligned with Western interests and was regarded as the first form of a state that would later pave the way for Israel a “proto-Israel”. This was articulated by the thinker Abdullah Ocalan (1949–) in The Manifesto of Democratic Civilization: “Zionist nationalism first constituted itself in Anatolia (prior to the establishment of Israel) and extended its control under the cover of ‘White Turkism’ and Turkish nationalism. What is being referred to here is a smaller, primitive Israel.”

- Encircling the Soviet Union from the south. In accordance with this role, Washington accepted Turkey into NATO and reinforced its position as a barrier against any socialist–communist expansion into the Middle East. This function formed the ideological and political foundation of policies of extermination and forced assimilation directed against the Kurdish people, who were defined as the absolute internal enemy of the Turkish nation-state. The Turkish state was thus founded on a policy of denial the “Republic of Denial”.

This dynamic—combining service to capitalist modernity with the practice of internal repression—continued without any fundamental modification for an entire century, until the balances began to fracture with the end of the Cold War and the declining effectiveness of the nation-state as a tool for safeguarding the interests of global hegemonic powers.

Redrawing and Reengineering the Map of the Middle East

There is no doubt that the project to redesign the Middle East is not a recent development; rather, it is a prolonged process that effectively began with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, followed by the outbreak of the Second Gulf War, and the official collapse of the Soviet Union on 26 November 1991. The Madrid Conference (1991) and the Oslo Accords (1993) then laid the groundwork for a negotiation track between the Arabs and Israel, directly encompassing the Palestinian track and indirectly the Syrian–Israeli track. This occurred at a moment when the region appeared to be moving toward major political settlements under international sponsorship, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the United States’ singular leadership of the global order.

Within this shifting context, Turkish threats against Syria—particularly in 1998—came to the fore, culminating in the departure of the Kurdish leader and thinker Abdullah Ocalan, followed by his capture in Kenya in 1999 with the participation of several states. This episode constituted one of the most telling moments revealing the fragility of national sovereignty under regional and international pressure, and it served as an indicator of emerging alliances at the time and the beginning of a reordering of power balances in the Middle East.

The attacks of September 11, 2001, in the United States then ushered in a new phase of military interventions under the banner of the “war on terror.” The most prominent outcome of this phase in our region was the fall of the Baathist regime in Iraq in 2003, accompanied by the dismantling of the state and society and the ignition of deep sectarian and ethnic divisions whose repercussions remain evident to this day.

With the advent of 2011, many Arab countries witnessed waves of mass popular protests that came to be known in Western media as the “Arab Spring,” while the thinker Abdullah Ocalan described them, in essence, as a “spring of the peoples” aspiring to freedom and democracy. These uprisings led to the successive fall of Arab regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen, and plunged Syria into one of the most complex and devastating wars since the declaration of its independence in 1946.

Amid these transformations, the strength of what was known as the “Axis of Resistance” gradually declined, particularly in light of developments involving forces such as Hamas, following its operations on 7 October 2023 against Israel, and Hezbollah’s involvement in bearing the repercussions of Hamas’s attack. As a result, both parties sustained political and military blows and faced intensified regional and international pressure, ultimately weakening Iran’s role in several of its traditional spheres of influence.

This long series of transformations was most recently capped by the fall of the Assad regime, a pivotal moment that reopened fundamental questions about Syria’s political future, the form of the state, and the nature of the coming system. Once again, the country found itself at a historical crossroads, where competing projects clash: between the reproduction of centralized rule and the move toward new models based on decentralization and communal democracy.

These developments have ushered the global system into a phase of broad and comprehensive repositioning, accompanied by transformations that have turned the world into a “global village” and reshaped the instruments of international power. The Middle East has returned to the forefront of global attention as a region in need of political restructuring consistent with the contours of the new world order. To achieve this goal, it became necessary to move beyond the classical nation-state model established in the early twentieth century, as this state—given its size, borders, and closed structures—has become incapable of meeting the demands of global capital, which recognizes no boundaries, or of providing the stability sought by major powers. However, this process of transcendence has been, and remains, extremely costly, with the peoples of the region paying the primary price—foremost among them the Kurds and the Palestinians, as those who have suffered most from geopolitical maps drawn at their expense.

Perhaps the principal reason for the delay or faltering in implementing the new map lies in the clash of interests between global powers on the one hand and forces of the status quo within the region on the other. Each party seeks to secure a larger share in the forthcoming redistribution, which inevitably prolongs conflict and delays the completion of the new model. The direct U.S. intervention in Iraq in 2003 and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime constituted the first practical step toward implementing this new map, through the collapse of the nation-state model in the Middle East.

Subsequent events have confirmed the validity of this assessment, particularly in light of the 7 October 2023 attack and the brief Israeli–Iranian war that followed (twelve days), and then the subsequent fall of the Syrian regime—one of the last rigid embodiments of the nation-state in the Middle East. Thus, the region has been transformed into open arenas of tension and conflict that have not subsided up to the moment of writing these lines, with global and regional powers persistently working to redraw the shape of states, spheres of influence, and alliances according to a new vision fundamentally different from those that governed the past century.

The old structures are collapsing one after another, yet the new structures have not been born as democrats might hope. The peoples of the Middle East are now living through a difficult transitional phase, in which regimes recede and new forms of authority advance. It appears as though the global system is experimenting more than it is planning, in a region that has become the epicenter of political transformations on a global scale.

The Form of the System Currently Proposed for the Middle East

To redesign the Middle East in its new configuration, it is necessary to move beyond the traditional nation-state model that was drawn up in the early twentieth century. At the time, this model aligned with the interests of Western capitalist powers seeking to dismantle major empires (German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman) and reassemble them as bounded, national states that were easy to control. Today, however, this model is no longer capable of performing the same role, nor does it align with the interests of a transformed global capital that has become more globalized and increasingly in need of flexible entities that are politically and economically permeable.

The nation-state and its governing systems, as a highly centralized and inward-looking model, have become one of the principal obstacles to capitalist modernity’s ability to keep pace with global transformations driven by market demands and by Western capitalist civilization’s need for models fully compatible with its interests. Added to this are other constraints arising from the vast global trade network and multinational corporations, the development of advanced military technologies such as nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles, the accelerated flow of information due to technological advances such as the internet and, more recently, artificial intelligence, and the movement of economic capital through cross-border financial flows (global financial capital). Consequently, international powers are pushing toward new political models that transcend the nation-state in favor of more liberal, open, and flexible arrangements—such as smaller entities than those currently in existence, broad political decentralization, confederal or liberal systems, and functional divisions of power. From their perspective, all of these forms constitute practical alternatives to the nation-state, which is seen as a primary instrument for igniting conflicts and wars and generating instability, and is therefore no longer suited to the current globalization regime.

Herein lies the essence of the new policy being pursued: transcending the nation-state is not being achieved through democratic or emancipatory frameworks, but through traditional policies long employed by classical colonialism—foremost among them the strategy of “divide and rule,” which remains one of the preferred tools of global monopolies. Rather than building strong states, current policies encourage civil, sectarian, and ethnic divisions and redistribute power in ways that produce weak, easily penetrable political entities aligned with the flows of global capital (and thus controllable when needed).

It becomes abundantly clear that the present phase is not one of state-building, but of recalibrating the region in line with the imperatives of the dominant global system as it rearranges its spheres of influence. Accordingly, all ongoing changes—from the collapse of nationalist regimes, to rapid wars, to the rise of alternative forces—are components of a comprehensive reshaping process whose objective is not to resolve the Middle East’s problems, but to establish a sustainable formula for protecting the interests of major powers within it.

Therefore, what is being advanced today in the Middle East is not a new system in the historical sense, but rather a functional framework for managing hotspots, engineering flexible local regimes, and laying the groundwork for a geopolitics that can be adjusted whenever the interests of global capital so require. What underscores this reality is that all projects currently proposed by states influential in and over the region—whether they take the form of new national entities, decentralized systems, or security arrangements—are not grounded in the needs of the peoples, but in what serves the interests of major powers alone. These include projects such as the Greater Middle East Initiative and the U.S. concept of “creative chaos,” the “New Middle East,” followed by Israel’s “Deal of the Century” and the Abraham Accords, Turkey’s neo-Ottoman “National Pact” project, Iran’s “Shiite Crescent,” and projects associated with Salafi political Islam.

Israel and the Role Assigned to It in the New Middle East

When Israel was tasked—according to the strategic conceptions of international powers—with becoming the central actor in the new phase of reshaping the Middle East, it became necessary to dismantle and weaken all structures that could pose an obstacle to this role or a threat to its security and political interests. Accordingly, Israeli targeting began to focus on forces that run counter to its regional project, foremost among them Hamas, followed by Hezbollah, extending to the Syrian regime—which, despite its fragility and weakness in recent years, represented a model of governance that challenged Israel’s future regional arrangements—and, subsequently, Iran.

The military and political developments witnessed in the region following the 7 October 2023 attack, and then the brief war that erupted between Israel and Iran and lasted twelve days in June, reaffirmed Israel’s position as the actor most capable of achieving decisive outcomes on the ground and setting the pace of events. Although this war was relatively short, it offered a model for the nature of future conflicts in terms of speed and precision, as well as the particular mode in which Israel operates against parties it regards as direct adversaries or potential Iranian proxies.

In this context, it became imperative to strike or contain forces linked to Iran, most notably Hezbollah and Hamas, as its leading regional arms. As Iran’s ability to protect or support them in the usual manner declined, it became evident that dismantling these structures was part of a broader strategy aimed at preparing the “New Middle East” in accordance with an Israeli security-first approach.

In parallel, Israeli pressure increasingly turned toward Syria as one of the principal strongholds of Iranian influence. Weakening or toppling the Syrian regime represents a strategic blow to Iran and opens the way for new maps that do not include centers of resistant power (the so-called Axis of Resistance) and do not pose a future threat to Israel. Thus, the Syrian regime became a political and security target—not because it constituted a real danger to Israel in recent years, but because it is part of a regional structure slated for dismantlement in order to make room for what may be described as a new arrangement based on clearly defined functional roles for new forces and systems that serve the interests of Israel and global financial capital.

Israel’s role has extended beyond the boundaries of conventional military confrontation to include targeted operations on 9 September 2025 against figures from Hamas in Qatar—an extremely significant development, as it explicitly indicates that Israel has crossed lines previously considered “red,” and that it is prepared to reach all actors regardless of their location or international relationships. This message was directed equally at Turkey, which is viewed as the most prominent ideological and political patron of political Islam movements in the region for more than a decade, and as a potential regional competitor to Israel.

The targeting of Hamas leaders in Qatar was not merely a security operation but a strategic signal that Israel now sees itself as the actor with the greatest freedom of movement within the region, capable of imposing new rules of the game without substantive objection from major powers. This coincided with its success—through a series of complex operations, significant U.S. pressure, and Egyptian–Qatari mediation—in pressuring Hamas to release Israeli hostages.

Israel’s targeting of Hamas leaders in Doha also refocused attention on the sensitivity of Qatar’s role, not only as a political mediator but as an influential global financial and energy power, particularly in the gas market. The event carried multiple security and strategic messages, foremost among them casting doubt on Qatar’s ability to remain a “balanced mediator” between the “Axis of Resistance” and the West. Under the pressure of these transformations, Doha found itself closer to a calculated repositioning within the U.S. umbrella, by strengthening its security and strategic understandings with Washington—extending beyond the current conflict to encompass the coming phase of U.S.–China competition. This reflects a shift in regional alliance priorities.

The evolution of Qatari–American relations following the targeting of Hamas leaders introduced a degree of tension into the balance network linking Qatar with both Iran and Turkey, particularly in files related to Palestine and Syria. Deepening security ties with Washington impose stricter limits on Doha’s room for maneuver with Tehran and recalibrate the tempo of coordination with Ankara in line with NATO priorities.

In this context, Israeli policy emerges as the primary beneficiary of the dismantling of old alignments. Paths toward what might be termed “quiet normalization” in the region are being reopened, and the Syrian file appears, in the medium term, to be a candidate for entering into undeclared understandings—especially in light of the structural transformations underway within the new system and its pragmatic discourse toward the West. However, translating these indicators into an openly declared political reality remains contingent upon the balance of forces within Syria and popular and regional reactions.

In this sense, Israel’s assigned role in the new Middle East can be understood as that of the driving center around which the elements of regional balance are being reshaped. Any power, structure, or faction perceived by the Israeli project as a threat is curtailed or struck, while the path is opened for new entities more aligned with the project’s strategic vision.

In short, Israel’s current role is not limited to self-defense or traditional deterrence, but encompasses:

- Eliminating the regional environment of existentially hostile and opposing forces.

- Dismantling structures inherited from the now-outdated nation-state era.

- Redistributing power and influence in the region in a manner that positions Israel as the decisive actor.

- Preparing the regional arena for new political maps consistent with both U.S. and Israeli interests.

Iran’s Role Between Yesterday and Today

When the Middle East was designed in the aftermath of the First World War, Iran—alongside Turkey—was assigned a central role within the regional balances crafted by the colonial powers. Together, the two states constituted a forward flank in regulating the region and preventing any undesirable shifts, particularly the later expansion of Soviet influence. To this end, the Shah’s regime in Iran was supported and protected politically and economically for six decades, as a cornerstone of stability from a Western perspective.

However, despite the support it received, the Iranian regime proved unable to withstand internal and social transformations and collapsed in 1979 in what became known as the victory of the Iranian Islamic Revolution. Thereafter, a widespread belief took hold that the region was headed toward an open confrontation between the West and the new Islamic Republic. What followed, however, was far more complex: direct tensions soon subsided, and a form of implicit balance emerged that allowed Iran to rebuild its regional position without a comprehensive confrontation.

Iran benefited from subsequent regional developments, particularly after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq in 2003. It expanded its political and military influence and constructed broad alliance networks—on the one hand with the Syrian regime, and on the other through allied parties and armed movements in several countries, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, and Hamas to varying degrees. In this way, Iran became an unavoidable regional actor and succeeded in entrenching its presence in four Arab capitals, a development that alarmed international and regional powers, which viewed this expansion as a direct threat to regional balances.

The current moment, however, marks a pivotal shift in Iran’s position within the new map being prepared for the Middle East. With the escalation of regional conflict, the outbreak of war between Israel and Hamas, and then the brief direct war between Israel and Iran last June, it has become clear that Iran has become the primary target in the strategy of regional restructuring.

As long as Iranian influence remains present and effective, it is difficult—according to U.S. and Israeli perspectives—to reshape the region in line with the new vision. For this reason, Iran has been weakened externally through targeted strikes, while its influence has eroded internally as a result of simultaneous economic, political, and social pressures.

The most notable outcome of these developments is that Iran has lost a significant portion of its power networks, as reflected in the following points:

- A major decline in Hamas’s capabilities following the qualitative strikes it sustained from Israel.

- The destabilization of its ally’s position in Lebanon (Hezbollah), amid threats to disarm the group following the elimination of prominent first-tier leaders, including Hassan Nasrallah (27 September 2024), Hashem Safi al-Din (November 2024), Ali Karki, and others.

- Iran’s loss of its position in Syria after the fall of the Assad regime, representing a major setback to its regional role and influence.

- The curtailment of its influence in Iraq, coinciding with international and regional pressure on the federal Iraqi government, which in turn pressured Iran-aligned militias—now caught between escalation and withdrawal.

All of this has undoubtedly weakened the key leverage cards of Iranian policy, from the so-called “Axis of Resistance” to the nuclear file—long a central negotiating asset for Iran with Western states and the United States within the framework of the P5+1. This is particularly the case following the heavy strikes carried out by Israeli and U.S. forces during the bloody twelve-day war, which largely crippled Iran’s nuclear program, signaling a potential reshaping of the region’s geopolitical map.

Thus, Iran has found itself in a defensive position for the first time in more than two decades, with its options narrowed to two paths:

- Adapting to the new regional order and making substantial concessions.

- Venturing into a second confrontation that could be broader and far costlier.

While the future of the Iranian regime remains unclear, one certainty stands out: its former position has come to an end, and the new regional map does not appear prepared to accommodate a large regional power with extensive ideological and military influence such as Iran.

The loss of Syria, the decline of Tehran’s proxies across the region, and the blows dealt to its defensive infrastructure all indicate that the redistribution of power in the Middle East is now unfolding at Iran’s expense, and that the role it played over the past two decades is being dismantled step by step—within the framework of shaping a new regional order that leaves no room for traditional “resistance” powers.

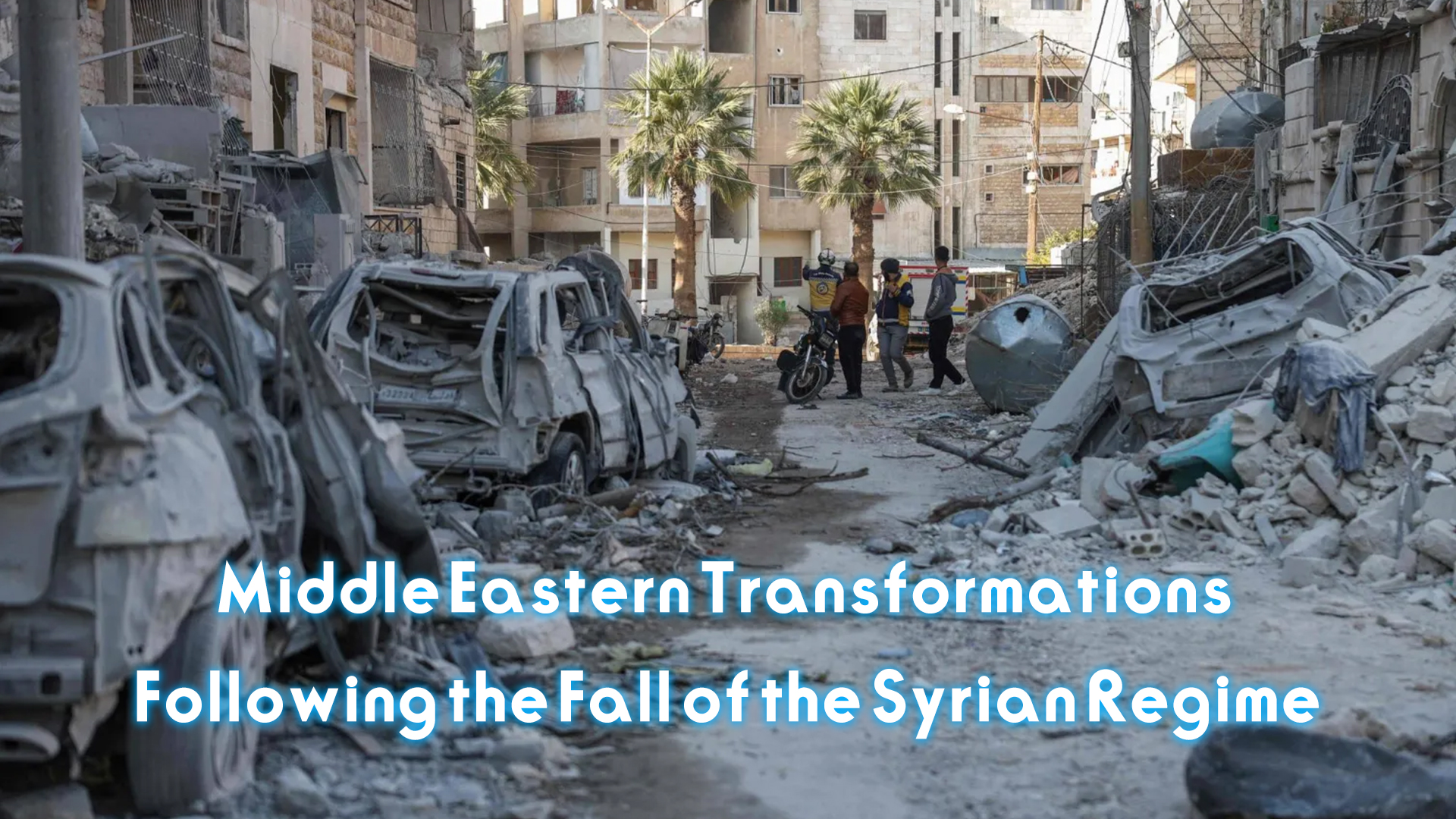

Syria One Year After the Fall of Assad

Syria today is experiencing one of the most historically complex moments since the beginning of the war over a decade ago, with political, security, and economic crises intertwining in unprecedented ways. Domestic developments intersect with deep regional and international transformations triggered by the fall of the Assad regime and the ensuing wide-ranging geopolitical changes that continue to affect the overall balance of the region.

Nearly a year after the collapse of the Ba’ath regime and the fall of Bashar al-Assad, Syria presents a tragic scene dominated by factional chaos, the disintegration of authority, and widespread violations against civilians. This occurs under a new form and mindset of governance, where force and weapons dictate logic, yet there is no substantive change in the authoritarian, inward-looking mentality. At the same time, Israel has emerged as the most influential actor in shaping the new rules of engagement in the Middle East, through a regional project aimed at fragmenting weak states from within and reorganizing spheres of influence in ways that serve its vision of regional security.

In this context, the control of Damascus by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) through the so-called “Syrian Interim Government” stands as a milestone highlighting the structural collapse of the Syrian state. This interim government, which adopted its own constitution and abandoned national state obligations in favor of a unilateral mindset, did not build modern institutions as it claimed. Rather, it has, to varying degrees, continued the Ba’ath regime’s project of fragmenting Syrian society and weakening its historical social fabric—particularly the diverse composition that shaped Syria’s identity for decades.

The factions under the Interim Government’s Ministry of Defense have committed massacres and widespread violations across all areas under their control, including the Syrian coast, Suwayda governorate, and the neighborhoods of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh, extending to attacks on the Alawite and Ismaili communities in Homs, Hama, and surrounding areas. Despite this, the Interim Government’s responses have been weak or nonexistent, revealing its inability to control or hold factions accountable. Simultaneously, near-daily Turkish threats against northern and eastern Syria—regions practicing pioneering democratic self-administration inclusive of all communities—demonstrate Turkey’s ongoing efforts to thwart any national or societal project not under its influence.

The situation is further aggravated by the Interim Government’s efforts to market itself regionally and internationally as the legitimate alternative, while fully overlooking violations committed by Turkey and Israel on Syrian territory, and ignoring crimes carried out by factions under its control in areas such as Afrin, the coast, and Suwayda. It promotes a sectarian and proselytizing discourse, including through mosques and media platforms, deepening societal divisions. Meanwhile, the government engages in political, military, and economic agreements with multiple states—primarily the United States, Israel, and Turkey—in ways that contradict any concept of national sovereignty, reflecting a pre-modern, or as some describe it, a “medieval” mentality in governance.

The massacres in the Syrian coast (6 March 2025) and Suwayda (11 July 2025) prompted sharp reports from international organizations. Human Rights Watch documented large-scale violations by government forces and allied armed groups, including mass killings, field executions, destruction of property, and mistreatment of detainees, noting that these crimes occurred within a centrally coordinated military operation under the supervision of the Ministry of Defense. These reports have increased international pressure on the current Damascus government to fulfill its duty to protect civilians and halt attacks against all Syrian communities.

The accumulation of these events illustrates that Syria today is not merely experiencing a political crisis but a comprehensive collapse of the state and societal system, with the disintegration of national reference points, governmental failure, and the absence of effective international intervention.

This situation requires national and democratic forces to move beyond merely monitoring events to adopting a comprehensive analytical vision that anticipates the future and outlines a realistic path out of the chaos. This includes implementing the provisions of the 10 March 2025 Agreement between the transitional phase president, Ahmad al-Sharaa’, and the commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces, Mazloum Abdi, as a first step toward restoring balance and stability across the country.

Reducing Turkey’s Role in Syria

The current developments in Syria cannot be analyzed independently of Turkey’s role and its direct influence on the course of military and political events. Since the onset of the Syrian crisis, Ankara has taken a serious and active stance, implementing a systematic plan to overthrow the Syrian regime by attempting to install an Islamist (Muslim Brotherhood) government, while simultaneously undermining any nascent advanced democratic experiment in Syria—namely, the Democratic Self-Administration established in 2014.

After failing to achieve these objectives and with the direct Russian intervention to support the regime, coupled with the successive defeats of ISIS at the hands of the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) in Kobani in 2014, Turkey resorted to direct military intervention. This included the occupations of Jarabulus in 2016, Afrin in 2018, and then Ras al-Ain (Sere Kaniye) and Tal Abyad (Kari Sipi) in 2019, with extensive participation from multi-national military factions that continue to operate according to their own agendas.

Amid these successive events, the balance of power shifted somewhat. The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) achieved consecutive victories against ISIS, including in Baghuz in 2019, considered the group’s last stronghold. Combined with the cohesion of the components of the regions governed by the Democratic Self-Administration in northern and eastern Syria under the principle of “unity in diversity and difference,” this significantly weakened Turkey’s policy. Consequently, Turkey continues to combat this experiment, fearing the spread of its democratic model among all Syrian communities. From Ankara’s perspective, any independent political model that includes Kurds, Arabs, and Assyrians, and is managed collaboratively with other groups, constitutes an existential threat to its nationalist and expansionist vision (the “National Pact” – “Neo-Ottomanism”).

Turkey’s role in Syria has centered on four main objectives:

- Undermining the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES): Ankara seeks to prevent the expansion and adoption of this political model by other regions in Syria, employing direct military attacks, supporting multiple armed factions as tools for this goal, and at times leveraging ISIS and its affiliates.

- Fragmenting Syrian Society: Turkey has pursued policies that sow ethnic, sectarian, and regional divisions to weaken a unified national identity and produce fractured communities that are easier to control.

- Consolidating Occupation through Proxy Factions: Turkey established a security, military, and economic infrastructure in northern Syria that relies on factions directly linked to it, turning the region into a functional extension of Turkish influence.

- Fomenting Tensions Among Syrian Communities: Through a sectarian and provocative media discourse, including via religious institutions, Turkey aims to erode trust among Syrians and exacerbate internal divisions.

In a significant development, the Turkish Ministry of Defense announced the start of training for the Syrian army and provision of military consulting under a memorandum of understanding signed in Damascus on 13 August. “Syrian soldiers will be allowed to use military barracks [in Turkey] for training to enhance their military capabilities.” This step is understood as an attempt to legitimize Turkey’s military presence by replicating a model similar to that previously used by the Syrian regime, which invited Iran and Russia to establish a presence under the pretext of shared strategic defense—effectively formalizing long-term occupation under military agreements.

However, this Turkish policy directly clashes with Israel’s strategy in Syria. In recent months, Israel has carried out precise strikes against Turkish military sites in Hama, Damascus, and Homs, sending a clear message that Turkish expansion—whether military or political—is unacceptable within the framework of the new Middle East. Israel views Turkish presence in Syria as generating three potential threats:

- The re-establishment of Islamist factions along its northern borders.

- A disruption of the Eastern Mediterranean balance, particularly regarding gas resources.

- Hindrance to the reshaping of Syria in ways that Israel deems suitable.

Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar warned global media in a direct message to transitional phase president Ahmad al-Sharaa’: “The cost will be high if you allow hostile forces to enter Syria.” This statement clearly indicates that Israel’s focus is not on the Interim Government but specifically on Turkey.

Similarly, Turkey’s absence from negotiations between Azerbaijan and Armenia under former U.S. President Donald Trump’s initiative to open the “Zangezur corridor”—a strategic route linking Azerbaijan to the Nakhchivan Autonomous Region via Armenia’s Syunik province, threatening Iranian and Russian influence—represents a major diplomatic setback. Observers note that excluding Turkey from this agreement diminishes its traditional influential role in the Caucasus and signals a broader decline in the effectiveness of Turkish foreign policy.

Turkey’s contradictions are particularly evident in its approach to the Kurdish issue: negotiating with Kurds domestically while existentially opposing them in Syria, politically and media-wise condemning them in international forums. Turkey’s strategy relies on:

- Shifting the international balance in its favor.

- Weakening the Democratic Self-Administration.

Yet, due to its deep-seated “phobia” of the Kurds, Ankara overlooks the evolving regional dynamics, which may render its project obsolete if the new regional system fully forms—especially given the SDF’s role in combating ISIS and its provision of tens of thousands of fighters.

Turkey has relied on local factions operating according to its Ottoman-inspired agenda—what Abdullah Öcalan described in his May 2025 book, Manifesto for Peace and Democratic Society, as Jewish mercenaries—groups that betrayed their people for foreign interests. These factions have acted as mercenaries, undermining any genuine national project and positioning themselves in opposition to Syrian interests while serving Turkey.

Thus, Turkey has become the most destabilizing factor in Syria, delaying regional reconstruction and any sustainable democratic institutional path—through both military interventions and the exacerbation of societal divisions.

Al-Sharaa’s Visit to the United States

Amid the rapidly evolving situation in Syria, the visit of Transitional President Ahmad al-Sharaa to the United States represented a pivotal moment that sparked extensive debate and varying assessments. Some observers interpreted the visit as a sign of formal U.S. recognition of the new leadership, while others viewed it more as a tool of pressure than a political endorsement.

In reality, the visit carried strategic implications that went beyond the usual political protocol, reflecting a shift in Washington’s approach to the Syrian dossier. U.S. policy now emphasizes recalibrating balances in Syria within the framework of the “New Middle East” project, signaling a move from managing the crisis remotely over the past decade to direct involvement in defining the rules of the transitional phase.

The invitation extended to al-Sharaa in Washington was therefore less about showing support than about testing his ability to align with, and operate under, the American vision. During the meetings, Washington focused on three key areas:

- Counterterrorism and Security Restructuring in Syria: This was a primary point of leverage to pressure al-Sharaa to reorganize relations with factions in northwestern Syria, particularly those connected to Turkey or holding extremist ideologies. The U.S. sought to gauge his willingness to sever ties with these forces and redirect efforts toward building a national security system.

- Limiting Turkish Influence in Syria: Washington aims for a transitional government capable of operating independently, without full subordination to Turkey, which the U.S. now sees as a regional actor conflicting with its broader strategic interests. U.S. pressure on al-Sharaa was intended to achieve a balance rather than allow Turkey to extend its influence.

- Commitment to the American Political Roadmap: The United States wanted assurance that al-Sharaa could pursue a disciplined political path, including cooperation with the Democratic Self-Administration, implementation of the 10 March 2025 agreement, and smooth integration of the Syrian Democratic Forces into the Syrian army—while ensuring Syria’s alignment with the international coalition against ISIS and avoiding alliances misaligned with U.S. interests.

Analyses accompanying the visit emphasized that the invitation itself was a form of pressure. Washington sought to convey to al-Sharaa that his legitimacy would not stem solely from internal Syrian approval or factional support, but from adherence to the vision of major powers. Many observers thus considered the visit a genuine test of his capacity to transition from transitional president to “statesman,” contingent on meeting U.S. and international expectations.

This transition is closely linked to Gulf support—particularly from Saudi Arabia and Qatar—which played a significant role in promoting al-Sharaa and his inner circle in Damascus. Substantial Gulf financial injections into U.S. markets strengthened Gulf influence within decision-making circles, which in turn shaped American engagement with Syria’s new leadership. As a result, al-Sharaa’s visit became part of a trilateral coordination: United States – Gulf – al-Sharaa.

Fundamentally, however, the visit conveyed a clear message: al-Sharaa must align with the U.S. regional trajectory, or risk being sidelined in favor of an alternative. The visit thus represented a highly sensitive political step, redefining al-Sharaa’s position in the regional landscape and demonstrating that the future of Syria’s transitional phase depends on his ability to navigate these pressures, rather than on the symbolic recognition afforded by the U.S. invitation and clear Gulf support.

Gulf backing during this visit also reflects an effort to test al-Sharaa’s ability to integrate into the emerging international order under U.S. conditions, particularly regarding regional stability, counterterrorism, and reconstruction efforts.

The presence of the Turkish Foreign Minister in the same context signals Ankara’s intent to cement its role as a political and security guarantor in the post-transition phase and to manage the pace of the transitional process to protect its strategic economic and security interests. This Gulf-Turkish convergence under the American umbrella suggests a pragmatic re-engineering of alliances, not driven by narrow ideology, but by a realistic approach to shaping a new phase for Syria and the broader region.

Summary:

The developments in Syria’s transitional phase reveal an extraordinarily complex reality that goes beyond the political collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, which ruled the country for more than five decades. This collapse has extended to deep failures in economic, social, security, and constitutional structures. Recent regional shifts—including the rise of new powers, the decline of traditional actors, and intensifying regional and international competition—have created a new landscape that requires careful analysis and a comprehensive understanding of the road ahead.

The fall of Assad’s regime does not merely signify the collapse of a despotic political and security authority; it has starkly exposed that the concept of the state had been hollowed out institutionally, reduced to the ruler and his security apparatus. The absence of institutional thinking and the erosion of free citizenship have deepened alienation between society and the state, turning the public sphere into a political and administrative vacuum. This void facilitated the emergence of multiple armed groups claiming to represent society by force, further fragmenting the national structure and, in effect, opening the door to direct regional and international interventions in determining the country’s fate, in the absence of a unified sovereign reference.

In this context, Turkey and Israel have emerged as the most influential actors shaping the transitional phase, albeit in opposing ways. Turkey has sought to impose its influence through armed factions aligned with its agenda and to legitimize its military presence through bilateral agreements. Israel, on the other hand, has acted to curb Turkish expansion through precise strikes designed to protect its security project in the region. Between these two powers, the Syrian Interim Government occupies a fragile position, lacking sovereignty and relying more on external patrons than on a comprehensive national project.

Ahmad al-Sharaa’s visit to the United States further underscores that political legitimacy in Syria is no longer domestically derived but contingent on the will of major powers. The visit functioned less as a show of support and more as a test of the new leadership’s ability to integrate into Washington’s vision for the New Middle East. This explains the explicit American pressures on issues such as counterterrorism, managing relations with Turkey, and adhering to the political roadmap outlined in the 10 March 2025 Agreement.

Against this turbulent backdrop, the democratic experience in northern and eastern Syria remains the most viable model. It has maintained a reasonable level of economic, social, and political stability through institutional mechanisms while promoting a political vision based on pluralism and community participation. Despite ongoing threats from Turkey, the self-administration stands out as the most mature and promising model capable of meeting the needs of Syria’s future.

The realities on the ground demonstrate that Syria cannot return to its pre-2011 state and that the rigid, centralized state model is no longer sustainable. Any political future for the country must be grounded in democratic decentralization, power-sharing, protection of communities, and the reconstruction of a moral-political society, as articulated by Abdullah Öcalan in his philosophy and paradigms. This requires redefining the state—from a tool of power and domination to an organizational-administrative framework for participatory societal life.

In conclusion:

Syria’s salvation does not lie in changing individuals or governments but in rebuilding the social contract on inclusive, participatory foundations that prevent the recurrence of past authoritarian models. The post-Assad phase presents a historic opportunity to reshape the country, while simultaneously exposing the depth of collapse produced by decades of repression and conflict. With overlapping interests of the United States, Israel, Turkey, and the Gulf, Syria’s future remains uncertain. True rebalancing, however, can only be achieved through an independent, comprehensive national project that excludes no one, beginning with the implementation of the 10 March Agreement, strengthening local councils, and building democratic institutions capable of protecting citizens—free from factionalism, sectarianism, and external dependence.

Syria now stands at a historical crossroads: either descending further into chaos or constructing a new reality founded on the will and aspirations of its people for a dignified life. This requires leadership capable of moving beyond traditional power mentalities and a vision rooted in the ethical and political values of society rather than solely in the calculations of regional and international powers. Syria’s future will not be secured through military deterrence or external bargaining but through the reconstruction of an effective society capable of self-governance and establishing new state-society relations—paving the way for a democratic, pluralistic, decentralized, and more just Syria for all its citizens.

Sources and References:

- Abdullah Öcalan, Manifesto of Democratic Civilization: The Kurdish Question and the Solution of the Democratic Nation, Volume V, translated by Zakho Shiar, 5th Edition, 2023.

- Human Rights Watch, Syria: March Atrocities Demand Accountability at the Highest Levels, published 23 September 2025.

- Independent Arabia website, 30 October 2025.

- BBC website – report by correspondent Lucy Williamson, 5 April 2025.

- Encyclopedia Britannica and Wikipedia.