Al-Sharaa’s Government and the Legitimacy of Power

Concept of Authority and Its Legitimacy

The field of humanities, in general, struggles with terminological challenges due to the diversity of methodologies and varying contexts of use. This complexity has contributed to the evolution of dialectics and the expansion of knowledge. The concept of authority is no exception to this phenomenon. For oppressed societies, authority is often a source of fear and anxiety, whereas, for democratic societies, it represents a source of security. This dichotomy suggests that authority is fundamentally rooted in a particular doctrine or belief system. This becomes evident in composite terms such as state authority, the authority of the ruler, the authority of the people, the authority of law, and the authority of religion, among others.

In this context, the concept of “legitimacy of authority” emerges as a critical issue, despite its foundational basis in the agreement between the ruler and the ruled[1]. Legitimacy relies on political, ideological, or natural law foundations, such as parental authority over children. Societal perspectives on authority and legitimacy differ due to variations in cultural, historical, and legal traditions[2]. A historical review of political systems reveals that the criteria for selecting rulers and maintaining their power are largely derived from the leadership selection traditions of each society. Every ruler is compelled either to rely on an established charter for legitimacy, impose a new framework, or justify their authority to ensure compliance with their orders.

Historically, three primary sources of legitimacy have influenced governance, evolving into theories that rulers have used to justify their power:

- The Sacred Basis of Authority (Theocracy)[3]

This theory posits that authority originates from divine sources. It manifests in different forms:

- Some rulers, like the Sumerians and Pharaohs, were perceived as divine beings.

- Others, such as medieval European monarchs, claimed to derive their power directly from God through divine right.

- Many Muslim caliphs were believed to be divinely guided, making them accountable only to God, rather than to their subjects.

In such systems, religious institutions play a crucial role in sustaining the legitimacy of rulers.

- Popular Sovereignty

This theory asserts that sovereignty resides with the people. Within this framework, two distinct models emerge:

- National Sovereignty Theory: Political power is concentrated in an elite group possessing material and moral strength, often derived from religious traditions, customary laws, and tribal hierarchies. Monarchical and feudal systems exemplify this model. Some cases also intertwine divine legitimacy, as seen in the Islamic practice of pledging allegiance to a caliph. A modern extremist example is ISIS, which coerced tribal leaders into pledging allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

- Popular Sovereignty Theory: This model grants all adult citizens the right to elect their leaders. Institutions such as parliaments or people’s councils play a decisive role in maintaining legitimacy within this system.

- Charismatic Leadership

In this model, the leader establishes legitimacy through personal influence and ideology, which then serves as the governing principle. This can occur through:

- Voluntary acceptance by the majority, as seen with revolutionary leaders, prophets, and intellectual visionaries who inspire followers through their charisma and vision.

- Coercion and manipulation, as seen in authoritarian and fascist regimes where rulers impose control through intimidation and incentives.

Historically, many legitimacy theories stem from past charismatic leaders—priests, philosophers, prophets, or military commanders—who crafted ideological foundations that later became cultural legacies, often justified as sources of justice or liberation from oppression.

The legitimacy of states has been codified in international law. Article 1 of the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States[4] outlines the fundamental criteria for statehood, which have become integral to international legal frameworks. These criteria require that a state must possess:

- A permanent population

- A defined territory

- A functioning government

- The capacity to engage in international relations

This classification underscores that a state must have three essential pillars: land, people, and authority—each interdependent. Furthermore, international instruments such as the UN Charter, international humanitarian law, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the statutes of the International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice define the boundaries of state legitimacy and governance.

However, international law lacks a definitive stance on issues of state fragmentation or the emergence of new states, as seen in the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Sudan.

Historically, the state has embodied a form of authoritarianism, wielding coercive power against dissenters, particularly when rulers monopolize authority. Many revolutions, initially driven by ideals of justice and equality, have devolved into authoritarian rule, prompting further uprisings. This pattern has contributed to the emergence of representative institutions such as parliaments and people’s councils, designed to balance power and ensure broader governance participation.

The New Damascus Authority and the Challenges of Gaining Legitimacy

The modern Syrian state is relatively young, having been established through the division of the region between France and Britain. The first government was led by Emir Faisal, who sought to justify his authority by invoking his Quraysh lineage and descent from the Prophet Muhammad—a claim rooted in the “divine mandate” theory of governance. This was a legitimacy that neither the Ottoman sultans nor the French occupiers could claim. After occupying Syria, the French attempted to establish a legitimate yet compliant government that would serve their interests. They adopted a “national sovereignty” approach by selecting feudal leaders to administer power. However, this strategy failed, as numerous uprisings erupted due to competition among feudal factions, many of which were led by landowning elites such as Ibrahim Hananu, Sultan Pasha al-Atrash, and Hajo Agha.

Following Syria’s independence, a form of democracy[5] was briefly implemented, but it was soon undermined by a series of military coups and the rise of extreme nationalist movements. This eventually led to the establishment of a fascist state that persisted until the collapse of the Ba’athist regime in late 2024.

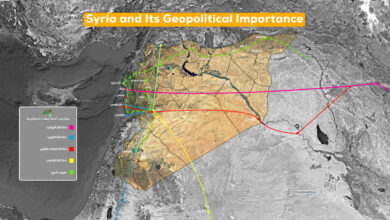

On December 7, 2024, Bashar al-Assad fled Syria after opposition factions from southern Syria—specifically from Daraa, Suwayda, and al-Tanf—entered Damascus with the backing of international forces, including the UK and its allies. Meanwhile, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) engaged ISIS in the Syrian desert, advancing west of the Euphrates and expelling Ba’athist regime forces and their affiliated militias. Simultaneously, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) waged intense battles in and around Homs.

On the day of Assad’s departure, a group calling itself the “Damascus Liberation Operations Room” broadcast Statement No. 1, declaring the fall of the regime. The group also secured foreign diplomatic missions and key government institutions in the capital. The following day, HTS leaders entered Damascus and began asserting their authority. One of the most significant events was the “Victory Speech” gathering on January 29, 2025, where numerous faction leaders pledged allegiance to Ahmed al-Sharaa as their leader. The next day, al-Sharaa delivered a public address, presenting himself as Syria’s new ruler. Observers noted that he fell into the logical fallacy of “appeal to authority” in his attempt to legitimize his rule[6].

Although Syria remains a recognized state under international law, successive governments have failed to establish lasting legitimacy. Now, HTS has positioned itself as the ruling authority over the remnants of the collapsed regimes. It has formed a government nearly identical to its previous “Salvation Government,” which governed Idlib and its surroundings under Turkish patronage. This connection became evident through frequent high-level visits by Turkish officials to Damascus, Aleppo, and other regions, as well as HTS’s friendly rhetoric toward Turkey, treating it as a de facto overseer.

Despite HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa’s assertions that they are moving beyond a revolutionary mindset in state-building, actions on the ground contradict this claim. The group has engaged in sectarian violence, including violations against Alawites, Christians, and Murshidis, as well as efforts to disarm the Druze. Furthermore, its veiled hostility toward Kurds, the SDF, and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) aligns with Turkish interests. These actions reveal that the factional, revolutionary mentality still dominates HTS’s approach to governance, especially in the absence of a national constitution.

The country remains mired in crisis, with widespread insecurity, and foreign forces continue to violate Syrian sovereignty. Turkish forces and their allied factions persist in targeting civilians in northern and eastern Syria, committing atrocities that human rights organizations have condemned. According to Human Rights Watch[7], “the Turkish armed forces and the Syrian National Army have a deplorable human rights record in Turkish-occupied northern Syria,” and many of these violations constitute war crimes.

Meanwhile, ISIS has capitalized on the power vacuum created by the regime’s collapse, escalating its operations and seizing weapons stockpiled by the former government. Syria also faces an acute economic and financial crisis. According to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA)[8], “approximately 16.7 million Syrians—nearly two-thirds of the population—require humanitarian assistance, with seven million internally displaced persons and rising chronic malnutrition rates.” The report also noted that Syria’s GDP has plummeted by 64% since the war began in 2011, while the Syrian pound lost two-thirds of its value in 2023 alone, pushing inflation to 40% in 2024.

Amidst these mounting crises, HTS leaders have unilaterally declared themselves Syria’s legitimate rulers. They have portrayed visits from Arab and foreign delegations to Damascus as endorsements of their authority. The group has also issued administrative decrees, dismissed numerous government employees, and used state-controlled media to reinforce its image as the new governing authority.

Political, social, and legal studies widely agree that any government’s legitimacy rests on three pillars: the people, the land, and sovereignty. However, the new Damascus authority lacks all three:

- The People – One-third of Syrians are displaced, and those who remain are deeply divided along political lines, each granting legitimacy to the faction that represents their views. Furthermore, the majority of Syrians, including Sunni Muslims of various schools, do not share HTS’s ideology. Additionally, the country is home to Yazidis and numerous Christian sects, none of whom recognize HTS’s rule. In a legitimate state, a national constitution should unite the people, but Syria lacks such a framework. Most Syrians have not consented to the new government through elections or representation by their political and social elites.

- Territory – Large portions of Syria remain under foreign occupation. Turkish and Israeli forces control significant territories, in clear violation of Article 11 of the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States[9]. Moreover, HTS cannot extend its authority over more than two-thirds of Syria, including the north, the south, the desert regions, and northeastern Syria.

- Sovereignty – True sovereignty is derived from the people and the land and is upheld through a legal framework. Philosopher Thomas Hobbes defined sovereignty as “the authority vested in an individual or a body to whom the majority has surrendered their will in exchange for security and stability.” Similarly, Islamic teachings emphasize that legitimate leadership is contingent upon justice, protection, and public welfare. Islamic jurisprudence states:

“The Quran and Sunnah outline governance principles that consider the people’s collective will in appointing and dismissing rulers. This is the fundamental measure of sovereignty.”[10]

Two months after HTS seized power in Damascus, it remains unable to exercise national sovereignty or fulfill its responsibilities as a governing body. Security remains precarious in its controlled areas, and it has yet to present a clear roadmap for consolidating power or curbing foreign interventions. Instead of hosting an inclusive Syrian National Conference to address the country’s crises, HTS hastily convened the “Victory Speech” summit on January 29, 2025[11]. At this gathering, HTS leaders dissolved all legislative, political, security, and military institutions of the Ba’athist regime and appointed Ahmed al-Sharaa (Abu Muhammad al-Jolani) as head of the transitional phase—without defining its structure or duration. He was granted unilateral authority to form security forces, an army, and a parliament, all without the participation of Syria’s broader political spectrum.

Syria Between a Citizenship-Based State and a Sectarian State

For over 70 years, the Syrian nation-state has failed to establish a stable and prosperous country. Successive regimes have been unable to transform Syria from an artificial state into a homeland for its diverse ethnic and religious communities by fostering a unified Syrian identity. To this day, deep-seated fears and anxieties persist among these communities—barriers constructed by extremist ideologies in the struggle for power and wealth over centuries. This reality is reflected in various conflicts, including attacks by Turkish-backed militias on Kobani, Tishrin Dam, Manbij, and Afrin, as well as power struggles among factions such as ISIS, Al-Qaeda, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Ba’ath Party. Furthermore, these groups continue to incite hatred against Kurds, Yazidis, Christians, Alawites, Shiites, and Druze.

Political, security, social, and historical indicators suggest that a citizenship-based state is the optimal solution for Syria’s stability and prosperity. However, current developments on the ground indicate a shift towards a sectarian state, especially with the establishment of a new authority in Damascus that lacks legitimacy, as it was neither formed through a national constitution, referendum, elections, nor with the approval of Syria’s political, social, and religious elites. Key indicators of Syria’s drift towards sectarianism include:

- HTS has enforced its ideological doctrine in the security forces and military training programs in its areas of control. Analysts at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies[12] argue that this move signals HTS’s intent to implement Islamic law across Syria. The new Damascus authority has consolidated security and military institutions under Sunni leadership, coinciding with the disbanding of Hurras al-Din, an Al-Qaeda affiliate, on January 28, 2025[13]. In a public statement, the group declared: “The Mujahideen of Al-Qaeda have supported the people of Syria in their struggle against oppression and in overthrowing one of the greatest tyrants of modern times, marking the end of a significant phase in the battle between truth and falsehood.”

However, the fate of its fighters remains uncertain. This dissolution aligns with HTS’s Ministry of Defense efforts to form a new Syrian army composed of various factions. Analysts warn that this integration will enable these fighters, as well as Turkish-backed factions and ISIS, to infiltrate the military structure, particularly given ISIS’s expertise in clandestine operations. Notably, ISIS recently issued a video statement on the “Al-Battar” platform, denouncing HTS leader Abu Muhammad al-Jolani as a traitor and threatening war if democracy is implemented in Syria. - The new Damascus authority has used Turkish pressure as a pretext to avoid engaging with the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in state institutions. Simultaneously, it is considering Turkish assistance in establishing its military forces. On January 30, 2025, the Turkish Ministry of Defense announced that a delegation had visited Syria to discuss security, defense, and counterterrorism cooperation.[14]

- The Damascus authority has failed to condemn or intervene against attacks by Turkish-backed militants on northern and eastern Syria, nor has it taken action against human rights violations committed against Kurds in Turkish-occupied areas.

- The new government has not issued any serious political statements to reassure non-Sunni Arab communities. Furthermore, it has yet to gain their acceptance, leaving them vulnerable to hostile actions and rights violations. Reports indicate ongoing abuses in rural Damascus, Hama, Homs, Latakia, and Aleppo. Additionally, HTS-affiliated media outlets and social platforms continue to broadcast sectarian rhetoric against these communities.

- The new authority in Damascus seeks to maintain its grip on power by adopting a pragmatic balancing act between Turkey and Arab states, Western nations and Islamist movements, and various military factions in Syria. This approach aims to leverage shifting power dynamics in its favor.

If Syria continues its transformation into a sectarian state, the Damascus administration will inevitably face conflicts on multiple fronts, both domestically and internationally. Currently, it lacks the capability to engage in such a struggle, and it is fully aware of the international stakes involved. Notably, HTS was once part of ISIS before its split, making the current leadership highly cognizant of the fate of the ISIS caliphate.

Consequently, the new administration is likely to maintain a strategy of appeasement, exploiting rivalries to its advantage while avoiding direct engagement in conflicts that could jeopardize its position. This is evident in its silence on National Army militia attacks against the SDF and Kurdish populations, its inaction against extremist violence targeting Alawites and Christians, and its attempts to portray itself as a neutral security guarantor.

This ambiguity extends to key geopolitical issues, including counterterrorism efforts, relations with Turkey, Russia, Iran, and Western countries, and the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 2254 on democratic governance. So far, the government’s stance has been limited to diplomatic niceties and unfulfilled promises.

The Crisis of Legitimacy

The new authority in Damascus lacks legal and political legitimacy to govern Syria or enact laws and treaties on its behalf. Several indicators highlight this:

- Failure of Turkish-led maritime border negotiations with Syria

- Inability to convince the UN Security Council of its capacity to enforce the Disengagement Agreement with Israel

- Saudi Arabia’s refusal to grant full diplomatic protocol to the new leadership during its visit to Riyadh

- Limited foreign aid—primarily humanitarian assistance with unclear distribution mechanisms

- Failure to secure financial grants, sanctions relief, or economic recovery measures

- Rejection of its authority by major Syrian power centers, including the AANES, Suwayda and Daraa leaders, coastal region communities, and a significant portion of Syria’s secular opposition

The Future of Syria: Three Possible Paths

As Syrians stand at a crossroads, three potential outcomes emerge:

- A Sectarian, Authoritarian State: A continuation of totalitarian rule, but with an intensified sectarian agenda.

- A Citizenship-Based State: A transition toward inclusive governance that upholds equal rights for all Syrians.

- Prolonged Crisis: Continued instability, with no decisive resolution in sight.

The year 2025 will be critical in determining Syria’s trajectory. Regional and international political, economic, and security dynamics, alongside the organization and influence of democratic forces, will shape the country’s future.

[1] Raad Abdul Jalil (Assistant Professor, PhD) – The Concept of Political Authority: A Contribution to the Study of Political Theory; Published by: Center for Strategic and International Studies / International Studies Journal, Issue 37, (No publication date); p. 127. Link

[2] Koran Aziz Mohammed Kakni (PhD) – The Concept of State Sovereignty Amid Changes in the International System: An Analytical and Future-Oriented Perspective; Published by: Anbar University Journal of Legal and Political Sciences, Vol. 14, Issue 2, September 2024.

[3] Political Encyclopedia (Online) – The Concept of Legitimacy; Published on: April 26, 2021. Link

[4] University of Oslo, Faculty of Law – Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States. Link

[5] The Syrian Constitution of 1950

[6] A person commits the “appeal to authority” fallacy (ad verecundiam) when they accept a claim solely based on the authority of its source rather than on evidence. While the claim itself may be true, the fallacy lies in treating authority as a substitute for proof or as proof itself. For further reading, see:

Adel Mustafa – Logical Fallacies: Essays in Informal Logic; Published by: Hindawi Foundation, York House, UK, 2019. (No edition number).

[7] Human Rights Watch – Northeast Syria: Apparent War Crimes by Türkiye-Backed Forces; Published on: January 30, 2025. Link

[8] United Nations News – A Defining Moment in Syria’s History: Reconstruction and Reconciliation or Chaos; Published on: January 25, 2025. Link

[9] Article 11 states: “The contracting states affirm, as a guiding principle of their conduct, a strict commitment not to recognize territorial acquisitions or special advantages obtained through force—whether by military means, diplomatic coercion, or any other effective pressure. The territorial integrity of a state is inviolable and must not be subjected to military occupation, coercive measures, or any form of direct or indirect external imposition, regardless of the justification or temporary nature of such actions.”

[10] Hanan Imad Zahran – Dissecting the Concept of Sovereignty; Published by: Arab Democratic Center for Strategic, Economic, and Political Studies; Published on: March 27, 2019. Link

[11] BBC Arabic – Syrian Authorities Announce Army Dissolution, Suspend the Constitution, and Appoint Al-Sharaa as President; Published on: January 29, 2025. Link

[12] Ahmad Sharawi – Syrian Government Uses Islamic Teaching to Recruit, Train New Security Forces; Published by: Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD); January 28, 2025. Link

[13] Alhurra – The Decline of Al-Qaeda’s Branch in Syria: Who Are “Hurras al-Din”?; Published on: January 29, 2025. Link

[14] Anadolu Agency – Turkish Military Delegation Discusses Security, Defense, and Counterterrorism in Syria; Published on: January 30, 2025. Link